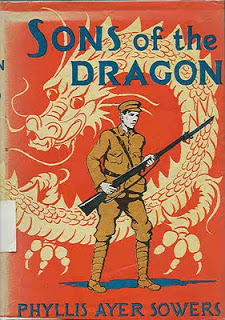

‘Sons of the Dragon’

- By Guest blogger

- 10 June, 2014

- No Comments

Like Pearl S. Buck, Phyllis Ayer Sowers spent much of her life living in China and other Asian countries and has written several books for children set in these countries. Sons of the Dragon was written in 1942. It is basically about how the Second Sino-Japanese War, which began in 1937, affected lives of two families, but the actual story begins a few years earlier.

Wu Liang is also in the Chinese army and, like Eddie Ching, he is angry and impatient with General Chiang’s attitude towards the Japanese, but becomes even angrier when he learns that Peiping (now Beijing) is being bombed by them. In the army, he is engaged in committing act of sabotage against the advancing Japanese whenever possible. While carrying secret documents by plane to the government in Nanking, Liang finds himself near home when the plane crashes. He discovers that the Wu ancestral home has been burned to the ground by the Japanese, with no survivors. He runs into Moonflower and there is an instant attraction, but he must leave to deliver the documents he is carrying to Chiang Kai-Shek in Nanking.

Wu Liang is also in the Chinese army and, like Eddie Ching, he is angry and impatient with General Chiang’s attitude towards the Japanese, but becomes even angrier when he learns that Peiping (now Beijing) is being bombed by them. In the army, he is engaged in committing act of sabotage against the advancing Japanese whenever possible. While carrying secret documents by plane to the government in Nanking, Liang finds himself near home when the plane crashes. He discovers that the Wu ancestral home has been burned to the ground by the Japanese, with no survivors. He runs into Moonflower and there is an instant attraction, but he must leave to deliver the documents he is carrying to Chiang Kai-Shek in Nanking.This can be a complicated novel, particularly for those of us not as familiar with the Second Sino-Japanese War as we probably should be. It certainly isn’t quite as interesting as Lisa See’s more recent Shanghai Girls, in which much of the action also occurs in 1930s China. I found the timeline in the beginning of Sons of the Dragon somewhat confusing and the flowery, often metaphorical language seemed unnatural. At one point, for example, Liang is asked the time, looks at his western-style watch and replies “Nearly the Hour of the Rat. That train is as slow as a lame donkey” (pg 39) I thought the language was a stereotypical portrayal of the way Chinese people spoke based on Western expectations.

Prior to World War II, China was a very patrilineal society and the names of the characters indicate this. Grown male characters names were simply Romanized versions of their Chinese name, like Wu Lliang or Ching Li, Moonflower’s father. The female character names and any young boys were direct translations of the character with no Romanization, so you have names like Moonflower, Lotus, Small Perfection (the son of Lotus), or Little Worthless. One would never call an adult male Big Perfection.

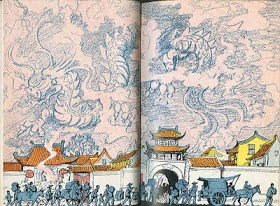

The novel is illustrated throughout with both black and white pen and ink drawings and a few color illustrations. They were done by the author’s sister Margaret Ayer, a writer and illustrator in her own right.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply