The Mysterious Greek – German Spies in China (3)

- By Peter Harmsen

- 17 December, 2016

- No Comments

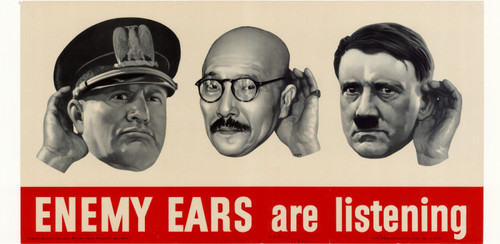

This is part of an occasional series on German espionage networks in China during World War Two.

This is part of an occasional series on German espionage networks in China during World War Two.

In 1943, one of the key German intelligence operations in China was a radio station run from a building in Shanghai’s Rue Petain. It was in the French sector, by then under Japanese control. Activities in the building all came to an abrupt halt towards the end of the year. Several of the German operatives were told to go on holiday and stay away for the time being. The reason, it transpired later, was that the building had to be used exclusively by a recently recruited spy going by the alias of Grosso.

Grosso had other code names as well, including Kross and Groesse, but the real name of this shady figure was Dimitrios Hyriakulis. He was born in Greece and had received Italian citizenship after working for Italy during its brutal occupation of Abyssinia in the 1930s. He had arrived in Shanghai in 1939 and had worked as a radio operator for Italy’s Far Eastern intelligence service until the Italian surrender to the Allies in 1943.

Italy’s exit from the German-led Axis threw Hyriakulis out of a job. This motivated him to start cozying up to the German agents working in Shanghai, and he found in the person of Bodo Habenicht, one of the senior Shanghai-based spies for the Reich. Habenicht was taken in by grand promises made by Hyriakulis. The Greek claimed to know a number of Allied codes not yet broken by the Germans, and he also said he had various Allied contacts.

Soon after he was installed at Rue Petain, Hyriakulis started producing reports based on what he said were coded Allied messages he had intercepted on the radio. His proud German handlers wired the reports to Berlin as soon as they could get hold of them.

Berlin, however, was not impressed. The feedback sent back to Shanghai criticized Hyriakulis’ reports for being highly inaccurate and argued that the wavelengths he had allegedly used to intercept Allied messages were downright “impossible.”

In other words, Hyriakulis seemed to be a fraud, and he was dismissed. Exactly what happened to him afterwards is not clear from the postwar records of the US intelligence services, which sought to map German espionage efforts in China. But when interrogated by the Americans, his handler, Habenicht, insisted that the Greek had acted in good faith, and that he had really believed in the value of his information.

The China-based German spies recruited not just Greeks, but also people of Italian, Dutch and Danish nationalities. One might ask why nationals of countries at war with or occupied by Germany would help German espionage efforts in China. Detailed information on their motives is not immediately available, but it is likely that for many of these individuals it was simply a job. A large number of people, including businessmen and sailors, had been stranded in China by the global war, and they needed work – any work – to generate an income and stay alive.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply