Military Attache: Witness to Carnage

- By Peter Harmsen

- 22 December, 2014

- No Comments

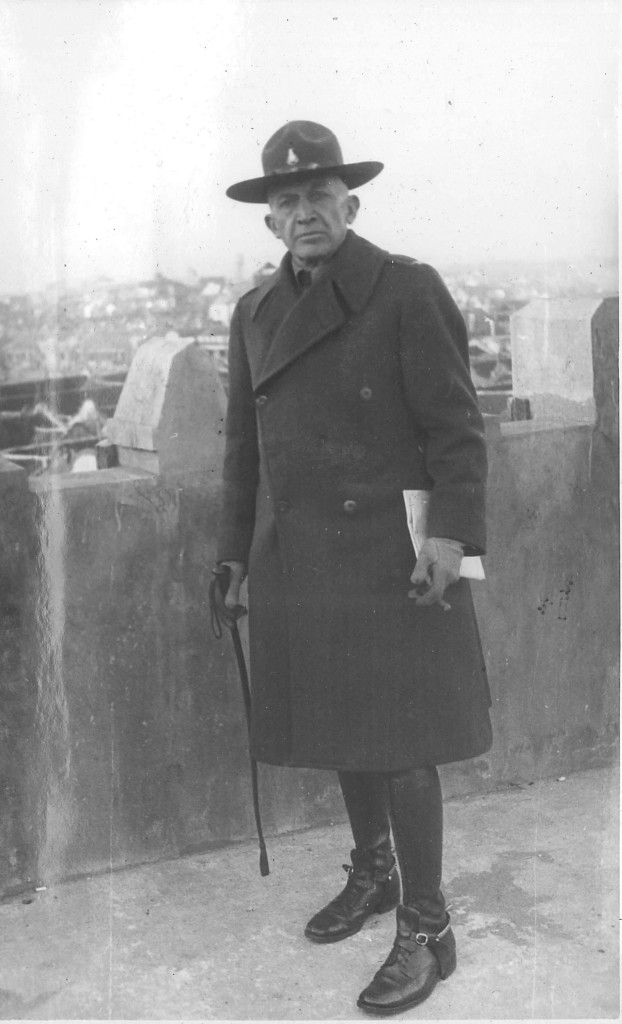

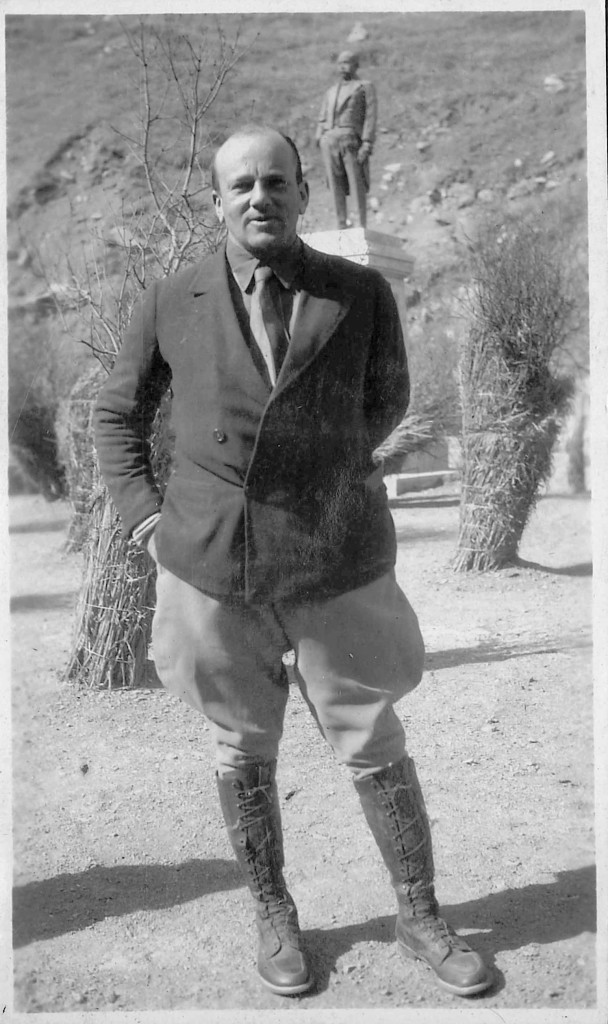

American Colonel William Mayer lived and worked in China from the 1920s to the mid-1940s, making him the archetypal old China hand. Luckily, one of the results of his quarter-century-long stay in China is a series of photo albums, offering unique insights into life in China in the first half of the 20th century. A small selection is reproduced further down on this page, all apparently from the same event.*) With no captions for these photos, identifying what is going on is somewhat of a challenge.

American Colonel William Mayer lived and worked in China from the 1920s to the mid-1940s, making him the archetypal old China hand. Luckily, one of the results of his quarter-century-long stay in China is a series of photo albums, offering unique insights into life in China in the first half of the 20th century. A small selection is reproduced further down on this page, all apparently from the same event.*) With no captions for these photos, identifying what is going on is somewhat of a challenge.

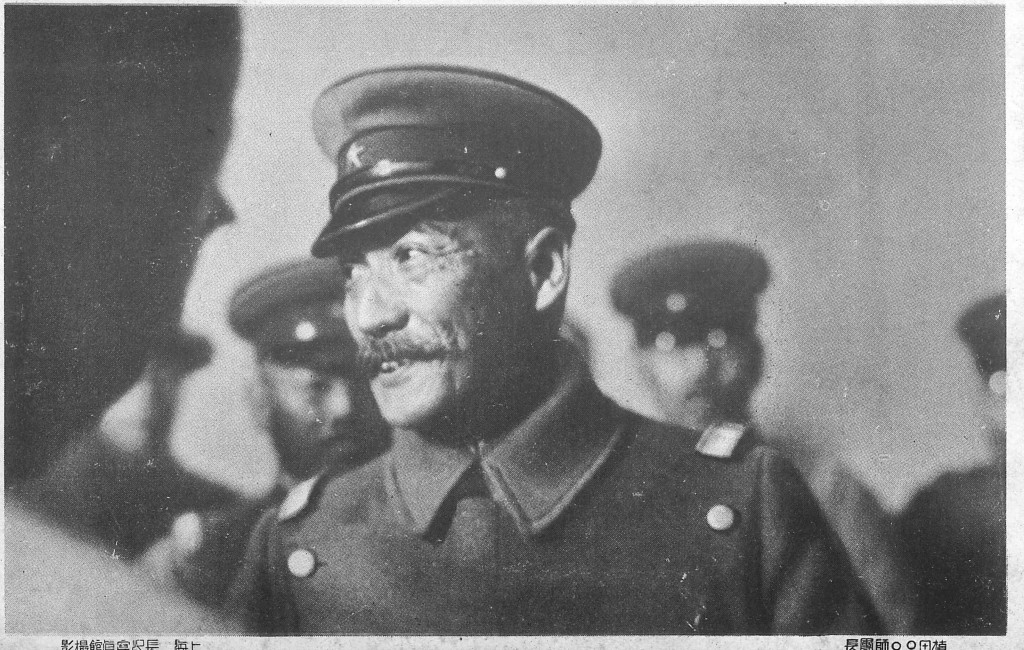

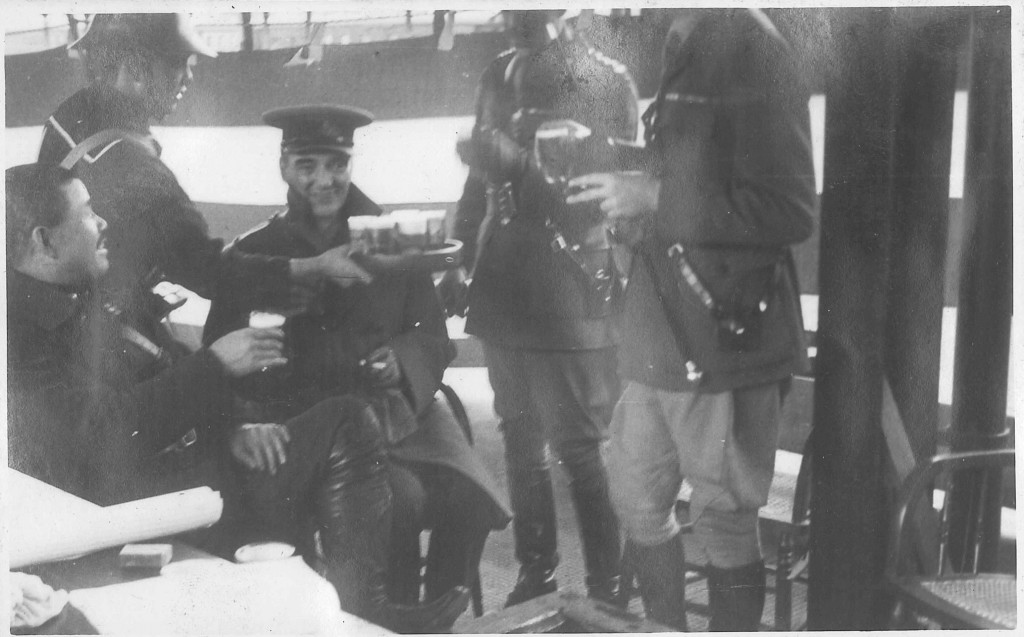

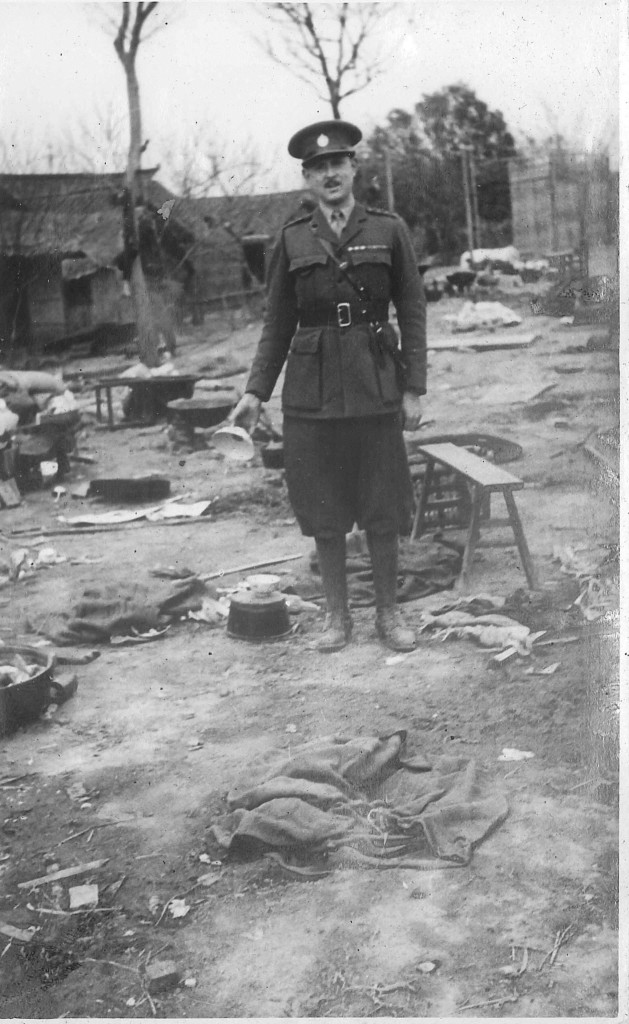

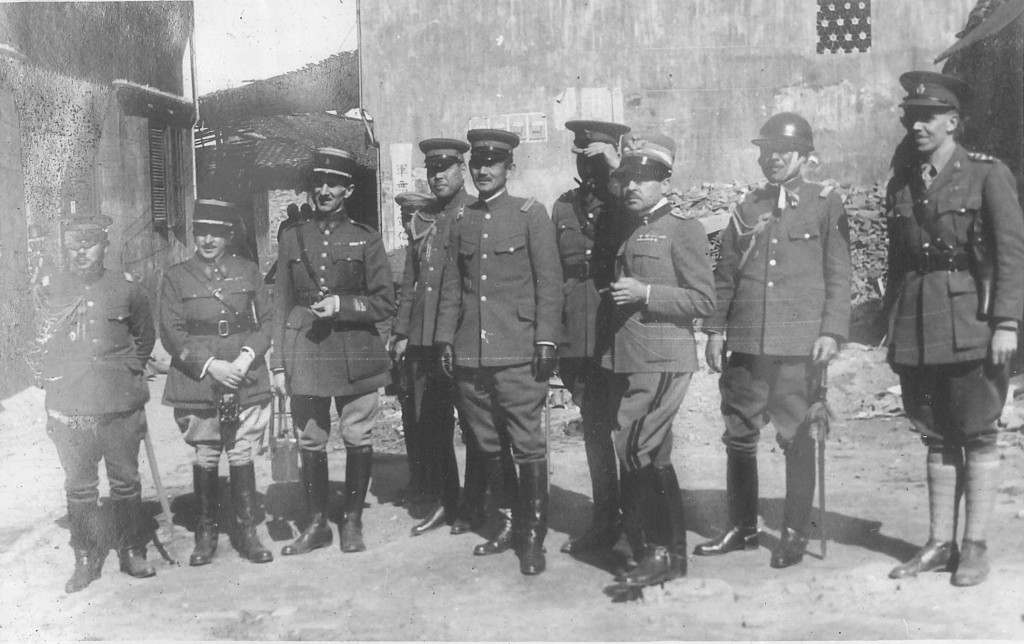

They appear to be from the first Sino-Japanese battle of Shanghai from late January to early March 1932, and show foreign military attaches visiting both the Chinese and the Japanese frontlines. Suspicions that these photos are from the first battle of Shanghai are strengthened by the thick clothing worn by most of the soldiers, consistent with fighting taking place in the middle of winter. In addition, a Japanese officer appearing in the album, while not identified, seems to be Ueda Kenkichi, who took over land operations in Shanghai in February 1932.

William Mayer, a captain at the time, was assistant military attaché at the US Embassy in Beijing, but was dispatched to Shanghai to observe the hostilities when they broke out. In this role, he appeared in the international media on several occasions. On February 2o, The New York Times reported that he had joined British, French and Italian officers in a protest lodged with the Chinese side over artillery shelling hitting the International Settlement, where most of Shanghai’s foreign population was residing. The Chinese commanders replied that the shelling had been in retaliation for fire from Japanese artillery batteries set up inside the Settlement.

One week later, The New York Times one again reported about William Mayer. This time it was because an old acquaintance of his, Chinese General Keng Wang, had turned up to visit his American friend at the building of the former US consulate in Shanghai, right next to the Japanese consulate. He did not know that the US consulate had been moved, and walked right into the arms of Japanese guards. The Chinese officer tried to escape, but was detained by the Japanese in the lobby of Astor House, a hotel in the neighborhood. The Japanese also got his briefcase, containing “highly confidential documents and military maps,” according to The Times.

Japanese officer, likely Ueda Kenkichi

Mayer appears to have had great sympathy for the common Chinese soldier and the hardship he endured when facing the technologically superior Japanese foe. While China’s 19th Route Army got most of the attention in the 1932 battle, he was eager to emphasize that the German-trained 87th and 88th Division – both to take part in the even bloodier Shanghai battle in 1937 – had done their fair share of the fighting.

As he wrote in a report to his superiors (reproduced here from Donald Allan Jordan’s excellent China’s Trial by Fire, p. 155): “Much credit has been given the Nineteenth R. A., which it is felt belongs to Chiang Kai-shek’s Guard Divisions. These divisions are responsible for the determined stand at Chiangwan. Much credit also belongs to the German training, which it is learned was based, in the preparation of defense positions, on the supposition that Chinese, poorly equipped, must prepare to hold lines against an enemy greatly superior in mechanical.”

*) All photos posted here are from the Virginia McCarthy and Lawrence W. Mayer collection of photographs from Isabel Ingram Mayer and Col. William Mayer. Also special thanks to William Mayer’s grandson Kenneth Mayer, who alerted us to these photos. He has posted a large number on Flickr (click here to access them), and would be grateful for any help in identifying who or what is on the individual photos. Suggestions can be sent to him directly or left in the commentary field below.

Three Japanese, one Italian. Note the elaborate knots that the officer on the right has used to fasten the helmet

Western and Japanese officers next to what could be a temporary shrine set up in honor of the dead in the recent fighting

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

Leave a Reply