The Japanese Girl

- By Peter Harmsen

- 19 September, 2014

- No Comments

Zhou Fukang was 23 years old when he met the love of his life. It was a brief encounter, and he never saw her again. At the age of 92, lonely and collecting garbage for a living, he is still dreaming about her.

Zhou Fukang was 23 years old when he met the love of his life. It was a brief encounter, and he never saw her again. At the age of 92, lonely and collecting garbage for a living, he is still dreaming about her.

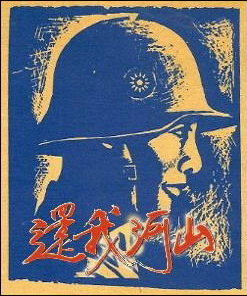

In 1945, he was a fresh-faced lieutenant who loved to sing. Serving in Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek’s army, he was among the troops sent to Taiwan to oversee the return of the island province to Chinese control after half a century as a Japanese colony.

This involved repatriating large numbers of Japanese, not just soldiers but also colonial administrators and businesspeople as well as their relatives. One of them was a pretty girl by the name of Henmi Sueko. She was a teacher at a primary school in northern Taiwan where Zhou’s unit was quartered, and she played the piano.

“She was so beautiful that I was immediately entranced by her and the music she played, and then we came to know each other,” Zhou told the Shanghai Daily. They didn’t speak each other’s languages, but Chinese and Japanese characters have much in common, and they communicated mainly by exchanging notes.

The budding romance was destined to be short. Henmi and her family were to be deported back to Japan by ship from the northern Taiwan port of Keelung. “I took a train there to bid her farewell,” Zhou told the paper. He said no one was allowed to see the Japanese, but he managed to get inside the restricted area due to his rank. That was the last he ever saw of her.

Ahead for Zhou were long years of suffering. He returned to the mainland to fight for Chiang Kai-shek in the civil war against the communists. His side lost, and he was later sentenced to 15 years of forced labor as a counter-revolutionary.

Japanese being repatriated from Taiwan in 1945

Finally released from incarceration, having barely survived, he was an “old man” of nearly 50. He never married.

Today he lives in his ancestral home in east China’s Hangzhou city, surviving by recycling garbage and also receiving a pension that the government has finally agreed to pay to veterans who fought the Japanese for Chiang Kai-shek.

The thought of Henmi is what has kept him going through all the years – even though she has perhaps been dead for nearly seven decades. He heard that a ship full of Japanese struck a mine just after leaving Taiwan in 1945. He doesn’t know if she was on that ship.

The story has become widely known in China in recent days, and a photo has gone viral of Zhou holding up a sign saying: “Henmi Sueko, where are you?” There has been no reply yet.

All in all, a sad story. And a story that reflects something more general about China and World War 2. How it never had a happy ending.

GIs would return to a country on the verge of an explosion in material wealth. German soldiers, once out of their POW camps, would go home to one of history’s most impressive economic recoveries. For the Japanese it was a similar story.

For other nationalities, the post-war years might have been more of a mixed blessing. British soldiers were facing an empire in decline and could look forward to years of scarcity. For the Soviet soldiers, there was a repressive society and a dysfunctional economy.

But the Chinese soldiers of World War Two appear to have been uniquely unfortunate. Having endured years of hardship and deprivation, in 1945 they could look forward to yet more years of hardship and deprivation – including periods such as the Cultural Revolution, when veterans who had fought on the side of the KMT were singled out for especially poor treatment.

It was only by the 1980s that China’s economy finally took off and started realizing some of its huge potential. It was late, and for old men like Zhou Fukang perhaps it was too late.

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

Leave a Reply