A Nanjing Martyr

- By Guest blogger

- 9 December, 2017

- 3 Comments

Marking the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Nanjing and the Nanjing Massacre this December, the new English translation of “Yang Dapeng: Remembrance of a Martyr in Nanjing 1937” is being released. Originally written in 1975 by the late Shu-Chin Yang, the book commemorates the author’s brother Yang Dapeng who died defending Nanjing as a young officer–and by telling this story of one soldier and family, seeks to keep alive the memory of millions of Chinese soldiers and families who perished in the War of Resistance against Japan in World War II.

Marking the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Nanjing and the Nanjing Massacre this December, the new English translation of “Yang Dapeng: Remembrance of a Martyr in Nanjing 1937” is being released. Originally written in 1975 by the late Shu-Chin Yang, the book commemorates the author’s brother Yang Dapeng who died defending Nanjing as a young officer–and by telling this story of one soldier and family, seeks to keep alive the memory of millions of Chinese soldiers and families who perished in the War of Resistance against Japan in World War II.

For nearly 40 years, Shu-Chin Yang had been haunted by the question posed by his family since the early days of World War II in China: “Where is Eighth Brother?” Yang’s brother Dapeng hadn’t been heard from since he entered battle after graduating as a young officer from the prestigious Whampoa Military Academy. Decades later, Yang finally faced the deep anguish of this early loss to launch an inquiry of his brother’s death at the Battle of Nanjing in 1937.

The book he wrote in 1975 seeks to give recognition to Yang Dapeng, who essentially died an unknown soldier, and in doing so, to commemorate all the soldiers of China’s War of Resistance who pitted themselves against a far stronger enemy to save their nation. The narrative, now translated into English by Shu-Chin Yang’s daughter, veteran journalist Catherine Yang, tells one family’s story in these unstable times–from engaging anecdotes of childhood in Northeast China to the tragedy of war. From a natural-born storyteller, this book is a poignant history and a valuable primary source about extraordinary ordinary people who lived through one of China’s most harrowing eras.

With the kind permission of Catherine Yang, we bring you this excerpt from one of the book’s early section, telling the story of how the family experienced the early 1930s, a time of growing Japanese intrusion into the north and northeast of China:

Finally, the colossal change we had all been expecting came upon us! In the middle of the night of September 18, 1931, we were awoken abruptly in our dorms by giant booms crashing non-stop. There was no need to say anything. We all knew this was a Japanese attack. Before long, we heard the Japanese Guandong (Kwantung) Army open cannon fire against the Army of Northeast China then stationed at the North Camp. We sat up and waited very quietly for morning to break.

After day break, I went to the First Commerce School (it was very close, and I didn’t need to walk on any big streets). I found Eighth Brother, and we went to our Fourth Aunt’s house. At that time, mother was staying with them on Xiaobeiguan Street. On our way there, we passed by Xiaoxiguan Street and spotted Japanese cavalry soldiers riding atop tall horses and cannon units rolling down the street, ordering people along the road to stop moving. Scared and revolted at the same time, we finally made our way through the streets, disappearing into small, empty alleys, passing by the tightly shut doors of various families, and finally arriving at Fourth Aunt’s house safely. Mother and Fourth Aunt were overjoyed that we had escaped and met up together. We learned later that the schools had closed down, and we never went back.

Puyi

Shenyang was given up to the Japanese without resistance. The Japanese Guandong (Kwantung) Army then advanced into western Liaoning Province. Soon, the roads near Shenyang were open again. Japanese soldiers never occupied Faku, which was not a particularly strategic location. Since our schools in Shenyang were closed and had no hope of opening any time soon, we decided to return to Faku. Shortly after we got back, a small group of Japanese soldiers moved into town. A few officers took up in my grandfather’s house and then left after a few days. Faku was handed to a self-governing body and local troops to run. Later we heard that the puppet state “Manchukuo” government had been established at Changchun. Puyi was the new “emperor,” and Changchun was now called Xinjing, or “New Capital.” China appealed to the League of Nations, which sent Victor Bulwer-Lytton of Great Britain to investigate. At ages 16 and 15, Eighth Brother and I were stuck at home, unable to go out, our days long, intolerable, and utterly depressing.

This period of humiliation for our country served to fire up our sense of purpose. Though Peng didn’t dare say it in front of others, his desire to enlist for military service grew stronger. Amid these days of boredom, he discovered a treasure trove of modern books and magazines in grandfather’s study, including the complete collection of Dongfang Zazhi, or East Asia Magazine (then the most respected current affairs periodical, published in Shanghai), subscribed to by my uncle. Among them were many articles about the Paris Conference, the Twenty-One Demands, and the May Fourth Movement.

Eighth Brother was most interested in the articles on military affairs. After reading them, he would tell me about various strategic military gains and losses. He knew all the uniforms of the different services and branches and the insignia of famous military leaders. He could recognize many types of tanks and firearms’ capabilities. Inspired by the fierce arms race among the world’s military powers, with all manner of warplanes placed into service, he made me assorted single- and double-winged warplanes out of thick paper, hanging them in the air at different lengths with kite string–some long and some short. Holding them in our hands, we would control the heights at which they flew to simulate air battles.

Meanwhile, I was also making use of our grandfather’s library by studying in depth Liang Qichao’s The Collected Works from the Ice-Drinker’s Studio, the novels of Lu Xun, Mao Dun, Ba Jin, and others, as well as Xiandai Qinnian (Modern Youth) and Zhongxue Sheng (Middle Schooler) magazines. These books and magazines profoundly inspired our world view.

Even without a school to attend, the two of us idle and bored, daily life had to carry on. In this era of the puppet emperor and pseudo-peace, Eighth Brother was referred to a job as a junior clerk at the district court in Tieling, while I remained in Faku. This was the first time we two had been apart for any length of time, and I couldn’t help but miss him. One day I was reading Robinson Crusoe in translation. Admiring Robinson Crusoe’s self-reliance and pioneering spirit, I wanted to try it out myself.

Faku is about 90 Chinese miles from Tieling. Cargo carts often traveled back and forth between the two towns, delivering agricultural goods. Soybeans and sorghum grown in Faku County and used for livestock were transported by horse or oxen cart to Tieling to be sold in big, tightly tied bundles. There, they would go by train to be sold south of the Great Wall or exported (mostly to Japan). A relative suggested I take a horse cart transporting sorghum (called da che, or big carts) to Tieling, so that I wouldn’t have to pay for travel fare. Right across the street from grandfather’s house was a big grain store, called Wandeyong, which we regularly looked after, and they readily agreed to my request.

Faku is about 90 Chinese miles from Tieling. Cargo carts often traveled back and forth between the two towns, delivering agricultural goods. Soybeans and sorghum grown in Faku County and used for livestock were transported by horse or oxen cart to Tieling to be sold in big, tightly tied bundles. There, they would go by train to be sold south of the Great Wall or exported (mostly to Japan). A relative suggested I take a horse cart transporting sorghum (called da che, or big carts) to Tieling, so that I wouldn’t have to pay for travel fare. Right across the street from grandfather’s house was a big grain store, called Wandeyong, which we regularly looked after, and they readily agreed to my request.

I left early the next morning before it got light. Sitting on top of burlap bags filled with sorghum, jostled left and right by the cart’s wooden wheels on the bumpy, dry, dirt road, I soon fell asleep. The road was so bad that we couldn’t even make 90 Chinese miles in a day. At noon, we stopped at a small village inn and ate a mouthwatering lunch, known as da jian, which included scallion pancakes, sautéed eggs, and Chinese cabbage soup. At night, we slept at another small inn, all the guests in one great room. The cart driver sat smoking a long pipe, chatting with other guests into the night. I fell asleep at first and then woke up. Hearing them tell terrifying ghost stories, I didn’t dare peek out from under my bed covers.

Early the next morning, we arrived in Tieling with no problem, and I saw Eighth Brother. He treated me to lunch in town with money he had earned himself. We were so happy with our reunion. He was very impressed that I’d travelled such a long distance on my own. But, I could tell with one look that Eighth Brother was unhappy with his job and circumstances. He was only 16, after all. How could he be expected to live his life among a group of corrupt officials? He wasn’t like them at all. He had even written a short article published in the newspaper about the corruption of puppet Manchukuo bureaucrats. The article had been well-received by readers. Brother’s writing and literary interests originated then, somehow evolving out of the dull work of copying calligraphy. Mr. Zhang Changyou said when Eighth Brother was at military academy, he often wrote in the military newspaper about loyalty and patriotism–that had its beginnings in Tieling.

In another heartening story, Eighth Brother had gotten to know an upstanding superior in the office, who liked Peng’s character, ambition, and articles. Sharing similar sentiments, they had a congenial relationship. I heard later that Peng had introduced this gentleman to one of our older cousins, and they got married.

Early the next morning I went again to find a grain cart to ride back to Faku, but this time, my plans didn’t run as smoothly. The carts had all left early. Those that departed later didn’t want to take me, because they didn’t know me. No matter, I was determined to walk home the whole way. At first, I strode with vim and vigor. Then after a while, fewer people were on the road, and I started to get scared. When I reached the mountains, I was especially frightened of the bandits and wolves that might be lurking. Robinson Crusoe had long evaporated from my mind. Instead, stories from old novels and Beijing opera of travelers held up for ransom started turning over and over in my head.

I had no weapons with which to defend myself. I could only resort to a thick stick that could help me walk and at the same time, do battle, if needed. By afternoon, I was dead-tired. My mouth and tongue were dry. From time to time, I would lay down on the fields by the road to sleep or bend down to drink from small springs. After sunset, I finally made it to the door of my house, dragging a pair of heavy legs across the threshold. My mother was so relieved. And at last, I had been able to see Eighth Brother.

Mother knew that I couldn’t stay idle at home forever, while Eighth Brother was in Tieling working as a law clerk. At that time, communications were open between the two sides of the Great Wall, and our eldest brother Jiayi sent word by telegraph and mail from inside the Great Wall suggesting we join him. Mother was afraid that the Japanese were keeping such close watch on young males that we couldn’t travel together as a family on the train from Shanhaiguan pass. So she arranged for Eighth Brother to go first. Luckily, Eighth Brother passed inspection and reached Beiping.

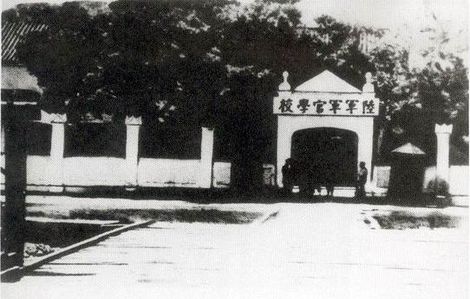

Whampoa Military Academy

Not long after, in 1934, he passed the exam to enter the Central Military Academy (also known as the Whampoa or Huangpu Military Academy) and was admitted on his first try. According to Zhang Changyou’s letter, only 650 students were admitted out of 10,000 top applicants that year in Nanjing (see Appendix IV). Though Peng’s formal education had been interrupted with our school closures in Shenyang after the 1931 Japanese invasion, he was still selected to be among the incoming cadets of Class XI. He was lucky to realize his life’s dream. Leaving work as a law clerk for the military academy, he literally “laid down the pen to take up the sword,” according to the saying. That year, he was 19.

A half year after Eighth Brother entered military academy, I also arrived in Beiping with mother. The whole family had found freedom, escaping the rule of Japan and the puppet Manchus. In the fall of 1935, we entered school in Nanjing. All three brothers were together. The nation was united and becoming strong day by day. Encouraging sights surrounded us everywhere.

Almost every Sunday, the three of us would eat lunch out together. This was the happiest time we had ever experienced together as brothers. Then, Mother returned to Faku to take care of her mother. But we reunited during summer vacation that year when my eldest brother and I went to Beiping, and mother joined us from the Northeast. We rented a summer house in the Fragrant Hills in the western suburbs of Beiping. Peng couldn’t join us because of his strict military training requirements. Though my eldest brother was recovering from illness that summer, we were very, very happy. Who knew that would be the last time I would see our mother?

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

As the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Nanjing approaches (December 10-12), the terrifying sounds of the war, which marked a milestone in the 60 years of Japanese aggression against China (and the people across Asia/Pacific) have fallen silent but the voices of the 20 million plus Chinese who perished, continue to echo in the hearts and memories of the greatest generation, and their descendants. These echoes have been given new voice by three recent publications: Rana Mitter’s Forgotten Ally, Peter Harmsen’s Battle of Nanjing and most recently by the English translation of Yang Dapeng, all available on Amazon, All three books provide critical perspectives on one of the momentous human struggles in History. This new release does much to personalizes the common human’s on the ground experience and is a valuable addition to learning the real story and lessons, despite the Japanese government’s Yasukuni-style denials and revisionism. This book is very easy to read and the author is a natural story-teller.

Wow! Great story!!

Yang Dapeng Remembrance of a Martyr is an epic and beautiful tribute to a hero, a brother, a son and a passionate brave soul. This story goes beyond just a historical tale set against a backdrop of an epic horrific time in history, that it is a true account of one young man and his family caught in a turbulent and brutal era makes identifying with with the pain of familial loss that much more searing.

This personal account of the author’s search for “8th brother” is both poignant and painful. Many may know the sense of loss when we lose a beloved sibling and friend – but to experience the not knowing gives more to grieve as there is no closure.

Shu-Chin Yang’s writing and this new English translation from his daughter Catherine Yang brings the feelings and imagery of the love of a close knit family, the love between siblings, the texture of personalities, the agony of loss and the relief of closure to life. There is something in this tale that all can relate to. This true story also serves to celebrate a young soldier’s life as brilliant as it was brief.

Yang Dapeng: Remembrance of a Martyr in Nanjing 1937 is a beautiful non-fiction story that is lovingly told. The reader will not be the same when the last page is turned.