Shanghai: Wicked Old ‘Paris of the Orient’

- By Guest blogger

- 24 August, 2016

- No Comments

“Keenly observant”, “riveting”, ” marvellous, microscopically descriptive” — the reviewers have rained down the superlatives on Canadian non-fiction writer Taras Grescoe’s new book Shanghai Grand: Forbidden Love and International Intrigue in a Doomed World. The subject matter is Shanghai before and during World War Two, as seen through the eyes of glamorous American journalist Emily Hahn. It was an exotic and dangerous place like no other – a world gradually descending into the maelstrom of war. In this exclusive Q&A with China in WW2, Grescoe talks about what attracted him to the subject, what surprised him during his research, and what we can learn from studying this distant, lost world lingering on the edge of living memory. Also read an excerpt from this great work of narrative history on Amazon.

“Keenly observant”, “riveting”, ” marvellous, microscopically descriptive” — the reviewers have rained down the superlatives on Canadian non-fiction writer Taras Grescoe’s new book Shanghai Grand: Forbidden Love and International Intrigue in a Doomed World. The subject matter is Shanghai before and during World War Two, as seen through the eyes of glamorous American journalist Emily Hahn. It was an exotic and dangerous place like no other – a world gradually descending into the maelstrom of war. In this exclusive Q&A with China in WW2, Grescoe talks about what attracted him to the subject, what surprised him during his research, and what we can learn from studying this distant, lost world lingering on the edge of living memory. Also read an excerpt from this great work of narrative history on Amazon.

The subject matter is very different from your previous books. What attracted you to writing about Shanghai in the 1930s and 1940s?

That’s true! My previous books have been, for the most part, non-fiction travel books, and firmly rooted in the present. The Devil’s Picnic, Bottomfeeder and Straphanger were polemical travelogues, in which I used my travels around the world to explore a particular issue (drugs prohibition, the impact of human appetite on the oceans, better urbanism through smart transport planning). During my travels, though, certain places caught my imagination, and I filed them away for future investigation. While doing the research for Bottomfeeder in 2007, I paid a visit to the Peace Hotel (the old Cathay) on Shanghai’s Bund. The sense of faded glamour was intoxicating. (As was the cocktail at the hotel bar, where I watched the Chinese musicians in the Old Jazz Band lurching through “Begin the Beguine” and “Slow Boat to China” one night.) I was also fortunate to get a guided tour of some shikumen alleyway complexes, the old Hongkong and Shanghai Bank of China building, and the Astor House Hotel from architectural historian Peter Hibbard. Peter really opened my eyes to how much of the historic architecture from the old Treaty Port days had survived into the twenty-first century.

When I returned home, I was haunted by what I’d seen in Shanghai. It struck me as a stage ready-made for gripping drama—or an intriguing work of historic non-fiction. I started to read about China in the 1920s and 1930s, and when I came across Emily “Mickey” Hahn, and her memoir China to Me, I knew I’d discovered an excellent eyewitness to Shanghai in its heyday as the wicked old “Paris of the Orient.”

Your book is full of colorful characters. Is there anyone in particular that stands out, especially during the three months of battle in 1937?

Shanghai attracted as bizarre a cast of schemers, exhibitionists, double-dealers, chancers, and self-made villains as has ever been assembled in one place. There was Trebitsch Lincoln, for example: born a rabbi’s son in Hungary, but who by the late 1930s had transformed himself into the “Abbot of Shanghai,” a shaven-headed Buddhist monk who, after a career as a double agent for the Kaiser, claimed he could marshal occult forces to help the Nazis win the Second World War. There was Morris “Two-Gun” Cohen, a Jewish brawler who grew up in Spitalfields before being shipped off to the Canadian prairies—where, after saving the life of a Cantonese cook in Saskatoon, he was inducted into an anti-Manchu secret society that would see him becoming the first foreign-born general in China’s Nationalist army.

The characters I was really grateful to encounter, though, were the journalists who were posted in China at the time—mostly because they were so rigorous about documenting what they’d seen. The Australian reporter Rhodes Farmer provides a particularly gripping account of the 1937 bombing of the Cathay Hotel in his book Shanghai Harvest. But the one who really sticks with me is Hallett Abend, The New York Times‘s man in Shanghai. He witnessed the war’s first explosions from his office in Broadway Mansions, and was shopping for a pair of field glasses when the Wing On Department store on Nanking Road was bombed, killing hundreds. After loading his severely wounded assistant into an ambulance, Abend made a beeline for the American-run Country Club. It was only as Abend gulped down a double brandy at the bar that he noticed a finger-sized shard of glass was protruding from his right foot.

In your research, which incident during the battle of Shanghai in 1937 surprised you the most?

Most surprising to me was the fact that the bombs dropped on Nanking Road and outside the Great World Amusement Centre on August 14, 1937, came from Chinese, rather than Japanese, planes. To this day, the world understands this as a Japanese atrocity—an impression reinforced, I think, by the famous photo, taken two weeks after the bombings, of the solitary Chinese baby bawling next to bombed out railway tracks taken by “Newsreel” Wong.

In fact, the Japanese were relatively scrupulous about respecting the borders of the International Settlement and the French Concession at the time. It was astonishing to me that the bombs that would eventually kill as many as 825 people were dropped by western-trained Chinese pilots—in other words, “Black Saturday” was a case of Chinese combatants killing Chinese (and western) civilians.

To his horror, US Air corps captain Claire Lee Chennault was a witness to the Cathay bombings. Brought to China by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists to advise on the formation of an air force, he’d decided to go up in an unarmed Hawk 75 monoplane to witness the fighting—in the midst of a typhoon. Chennault witnessed how the poorly-trained Chinese pilots, who were trying to score a hit on the Japanese flagship Izumo, released their bombs from too low a height. Gusts from the storm then blew their bombs right into the heart of one of the world’s most densely populated cities.

“Unknowingly,” he would write in his memoirs, he’d “set the stage for Shanghai’s famous Black Saturday—a spectacle that shocked a world that was not yet calloused to mass murder from the sky by thousand-plane raids or atomic bombs.”

“It’s just the natives fighting,” Vandeleur Grayburn famously or infamously said about the opening battles of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Does this describe the expat community’s view?

To a certain extent, it does. I was surprised to discover, for example, ads in the North China Herald and the Shanghai Mercury announcing the reopening of the Cathay Hotel only a few weeks after the bombing—and while the Battle of Shanghai was still raging. The latest Hollywood films were soon showing at the Grand and Cathay Theatres, and mail from the rest of China was still being delivered behind the barbed wire. Shanghailanders consoled themselves with the thought that conflict came to the city in five-year cycles and Shanghai would shrug off the fighting just as it had in 1927 and 1932.

But, among privileged insiders in the foreign community, there was an understanding that this time was different. Sir Victor Sassoon, whose diaries and letters at the DeGolyer Library in Dallas provide a vivid record of day-to-day life in Shanghai, was clearly aware that things were far worse than they had been in 1932. To staff, associates, and friends, he maintained a “business-as-usual” attitude about the fighting. In a letter sent at the end of 1937, though, Sir Victor was already anticipating a complete Japanese takeover of Shanghai. “Things are looking very serious now,” he confessed to a confidant in London. “Am not showing this letter to the Staff as I do not want them to know how depressed I am.”

Shanghai was a city of extremes even before the war. Do you think the advent of war had less of an impact on the general mood than in places like, say, Amsterdam or Warsaw a few years later?

It depends on which community you’re talking about. The “Shanghai Mind,” as Arthur Ransome described the locals’ hermetically-sealed imperviousness to events in China, meant that some Shanghailanders could go on playing tennis or going to their offices as though nothing was happening. Many even experienced the war as a spectacle—watching the fires in Zhabei burning as they sipped cocktails in the upper floor bars of the Cathay or Park Hotels.

But the bombings—even if they were accidental—upset many in the foreign community, and you can find the first signs that the legendary sense of security offered by foreign gunboats on the Huangpu River and the rifles of the multi-national Shanghai Volunteer Corps was starting to be questioned.

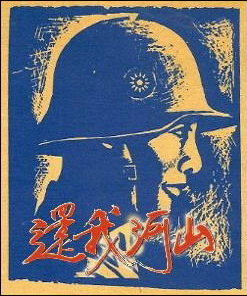

As for the Chinese, who suffered the brunt of the Japanese invasion, their mood couldn’t be worse. The only thing to cheer them was the occasional tale of desperate, heroic resistance. In 1932, it had been the surprising opposition of the ragtag 19th Route Army, who, armed with rifles left over from the Franco-Prussian War and grenades made of cigarette tins, provided stiff opposition to the Japanese for five weeks. In 1937, the Chinese were similarly encouraged by the “Lone Battalion,” five hundred or so soldiers who heroically held off the Japanese for four days by occupying the Joint Savings godown on Suzhou Creek.

By January 1938, though, the Japanese army’s atrocities in Nanking began to be known in Shanghai. At that point, any hope that might have buoyed the mood of the Chinese was replaced by horror and despair.

Writers on Shanghai in the 1930s and 1940s are blessed with copious historical sources. Was there any time when the sources were not quite sufficient, and you wished you could have gone back in time and asked the people who experienced the events to clarify or elaborate?

People who lived in Shanghai in the 30s and 40s seemed to be aware that they were witnessing a strange and wonderful phenomenon—a city that was at one the acme of cosmopolitanism and glamour, and a nadir of corruption, degradation and injustice. Day-to-day life in the city was recorded in copious detail by English, French, German, and Russian-language newspapers, but also in the journals, notebooks, letters—and eventually, memoirs—of foreigners, on whom the city seemed to make an indelible impression. (Some, like Aldous Huxley, Albert Londres, Vicki Baum, Christopher Isherwood, and W.H. Auden, were just passing through. Others managed to write about Shanghai without actually having set foot there; among them Hergé, whose Tintin adventure The Blue Lotus is partially set in the city, and André Malraux, who set the Human Condition in an International Settlement he hadn’t actually visited.)

With that said, there are gaps in the record. I wish I could have found the guest registries for the Cathay Hotel, which seem to have disappeared during the Cultural Revolution—they would have provided an invaluable record of who passed through the city, and when. And if I could interview one person from Shanghai’s salad days, it would probably be Lucien Ovadia. Sir Victor Sassoon’s cousin, and right-hand man, came to Shanghai in 1935, and became a virtual prisoner of the city after 1949, when he was forced by the Communists to remain behind as the old Sassoon property empire was slowly liquidated. I searched in vain for his diaries and papers. Of all people, the well-situated Ovadia would probably have known where the bodies (actual and figurative) were buried.

Can writing and reading about Shanghai in the 1930s and 1940s help us understand our own age better?

Yes—emphatically! It’s my thesis that to understand what the world’s going to be like tomorrow, you have to understand China today. And to understand today’s China, you have to know what Shanghai, its greatest city, was like yesterday.

Treaty Port Shanghai, after all, was the crucible for all the ideologies—western colonialism and Chinese communism, authoritarianism and nationalism, free-market capitalism and aggressive globalization—that forged Asian history in the twentieth century, and whose legacy is making history in the twenty-first.

A key and recurrent idea in Shanghai Grand is that Shanghai was born out of the trauma of contact with the West—and particularly the introduction of a pernicious trade good, opium, that further weakened a troubled empire at an unusually vulnerable time in its history. Cultural memory in China runs deep and long—and I believe that if you want to understand China’s immediate future, you have to understand the humiliating subjugations imposed on Chinese civilization by the opium wars.

In other words, untangle Shanghai in the twentieth century, and you have the key to China, and the world, in the twenty-first century.

With that said, though, Shanghai in the 1930s and 40s was just an outlandish, entrancing city—and one worth reading about in its own right. There’s never been a place like it, and there never will be again.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply