Flying ‘The Hump’

- By Guest blogger

- 23 April, 2016

- 2 Comments

This article, about one of the many American pilots who risked their lives to keep China supplied across the ‘Hump’ air route, is written by seasoned journalist George Morris. It is reproduced with his kind permission from his website WW2: The Big One. Check it out – it’s a gem, full of original interviews with veterans of the greatest conflict the world has ever seen.

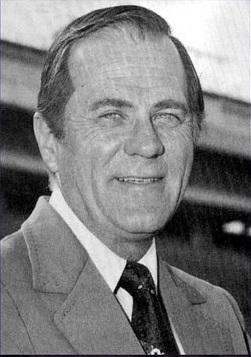

A generation of Louisiana State University fans knew John Ferguson as the play-by-play voice that carried the action of Tiger football into their homes and car radios. But in World War II, Ferguson wasn’t just on the air. He was in it.

Way up there, in a wild and wooly section of the sky over the world’s tallest mountains.

They called it flying “The Hump,” that being the understated description of the Himalayas. They ran cargo missions from India to China, helping keep the beleaguered Chinese in the war against Japan. It sounded simple enough. It was anything but.

Not only was this an era without GPS and sophisticated navigation systems, but one in which large swaths of the Himalayas were uncharted. Storms, ice, fog and the jet stream — then a little-understood phenomenon — created flight and navigation problems that could quickly turn a routine flight into a terrifying dance with death.

“It was, for pilots, the big leagues,” Ferguson said.

Kind of like Southeastern Conference football, but with graver consequences.

Between May 1944 and May 1945, Ferguson made 72 round trips piloting the four-engine C-87. Unofficial estimates after the war were that about 3,000 Allied airplanes did not come back.

“The enemy, of course, was the weather,” Ferguson said. “In that part of the world, the thunderstorms, which are frequent, are also extremely violent. I’ve seen tops of thunderstorms estimated at 80,000 feet on many occasions, which means the violence is multiplied by a factor of big numbers … We flew in the middle of them.”

From Jan. 4 to Jan. 8, 1945, a large storm settled between Allied air bases in northeast India’s Assam Valley and Chinese air strips at Kunming and Chengtu, causing aircraft instrument needles to spin in circles. Ferguson heard lost pilots on the radio begging for directions. In two days, 24 airplanes from Ferguson’s base, Jorhat, crashed.

“The whole sky looked like it was on fire from one end of the horizon to the other, and we couldn’t get over the stuff,” Ferguson said.

Ferguson might have been the 25th crash, but his co-pilot spotted Jorhat through a hole in the clouds. Ferguson cork-screwed the C-87 through that break. A thunderstorm socked in the airfield as soon as his wheels hit the runway.

“The moral of that story is you’re never by yourself. To this day I’m taken aback by that,” Ferguson said.

There were challenges besides the weather. Airplanes often were so heavy with supplies they were difficult to get off the ground. Some airstrips put steel matting at the end of runways. The matting provided a last-second springboard effect to help takeoffs.

“You’d go rolling down and pulling everything you could pull, and you’d come to that steel matting and all of a sudden ‘BAM-ch-ch-ch-ch-ch,’ and you’d bounce and finally get up and wiggle on into the sky,” he said. “If a pilot did that with me today, I might kill him. I really might.”

Ferguson said he flew as high as 30,000 feet in non-pressurized cabins. Temperatures at 60 to 80 degrees below zero were made more bearable when heated flying suits replaced heavy, fleece-lined apparel. But that was only for the crew.

One of Ferguson’s 72 trips involved taking several dozen Chinese soldiers to India for training. An unexpected turn in the weather forced Ferguson to fly higher than planned, close to 20,000 feet. His crew had oxygen. The soldiers didn’t.

“They’d come up to me and say, ‘Sir, all these people are going to be dead,’” Ferguson said. “I said, ‘I can’t help it.’… We stayed up there a good, long while.”

When they landed, Ferguson and crew, convinced the soldiers could not have survived, exited through the front of the plane rather than witness what became of them.

“I was sure all of them were dead, because they had been without oxygen for a long time,” he said. “The troops we had varied in ages from probably 12 to up in the 70s. They all wore cotton long pants and jackets and sandals with no socks and a little hat.”

After about two hours, they opened the rear cargo door.

“One by one over a period of, I guess, a couple of hours, those people came out and lined up in a ragged line. They were all alive,” Ferguson said.

“We all learned to cry that day.”

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Extremely moving tale of a great pilot who conquered the Hump. I have worked in Northeast India for Airports Authority of India & aware of the treacherous weather which has result in chopper crashes even today. Dec to Feb considered very safe for aviation in these parts with clear skies. Such thunderstorm in Jan 1945 would have been really unfortunate. I salute the pilots who braved the Hump & went down mostly unsung.

My grandfather, Arthur Fourment flew the hump and today is a spry 99 year old. Thanks to all who put everything on the line for the freedom we still enjoy.