Shanghai’s Invisible Stain II

- By Guest blogger

- 30 January, 2015

- No Comments

This is the second instalment in a two-part series about Shanghai’s dark legacy — buildings that housed brothels used by the Japanese Army during World War Two. This article, written by Sue Anne Tay, describes a visit to a large villa that served as a military brothel for years. It first appeared on her website shanghaistreetstories.com, a great resource for those who want to explore the rich history of China’s most cosmopolitan city. Also check out their Facebook page.

A nosy neighbor shared that a descendant of the Lin family still lived in the villa. I thought to seek him out as I climbed up the handsome stairwell that swirled up all three floors but couldn’t bring myself to interfere with the low hum of the television and giggling children behind closed doors. Instead, I admired the intricately carved banisters and sturdy newel posts, unfettered by everyday paraphernalia that were instead, messily draped on walls and in dust-lined cupboards. With so many families now inhabiting the space, the wear and tear was visible.

Still, the villa stood imposingly amongst its neighbors and embodied an elegant mix of European and traditional Chinese designs. Small touches of Deco sunburst rays and zig-zag framings lined the edges of the driveway entrance and the interior veranda ceilings. Rounded pillar moldings were a common theme woven across the exterior walls of the house, complimenting the elongated sweep of the south-facing balconies. Part of the interior floors were covered in black and white tiles dotted with Buddhist swastika symbols. Above the entrance leading into the family reception, a pair of beautiful stone lions(石獅) carvings supported the eaves of the balcony overhead, signifying the wealth of its former patrons.

Exploring the aspirational grandeur of the villa, I imagined a typical day in the life of Lin‘s family in the early 1930s: As master of the house, he would receive visitors in the front room to discuss his various business interests, drinking tea on the veranda on a cool summer evening. On the second floor, his wife was likely bickering in the stairwell with Lin’s concubine hovering haughtily on the third floor. With the continued absence of a son, Mrs Lin’s insecurities grew daily at the marital intrusion she had no choice but to accept. Meanwhile, servants bustled in and out of the back of the villa that connected with the rest of the lilong, cooking, cleaning and mending.

How would it later run as a Japanese comfort house? Archive photographs and survivor accounts described an eerily clinical environment where for low-ranked soldiers; sexual acts were conducted in large dormitory rooms with beds separated by thin curtains. Looks were rarely an issue for the pent-up and war-weary soldiers. The Chinese women were trapped and manhandled. Dressed in cheap Japanese kimonos, they had to endure routine examinations and were fed birth control by doctors who also checked them for venereal diseases. One survivor noted that her doctor would rape the girls after examination. Military personnel had even received accountancy classes on “how to manage comfort stations, including how to determine the actuarial ‘durability or perishability of the women procured.’” [1]

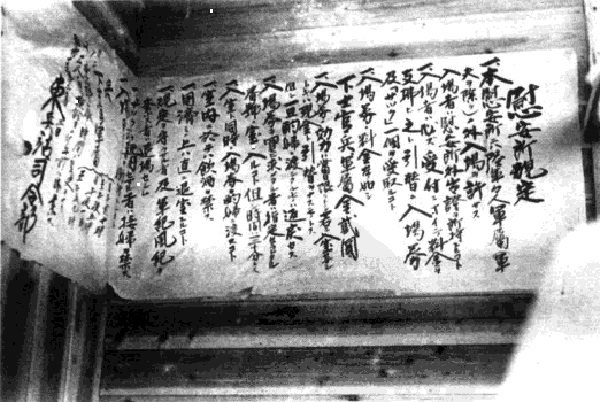

Like any military unit, every comfort house was run in a cold and orderly fashion, against the background of masculine grunts, creaking beds and muffled cries of women who have long lost their innocence. In Shanghai, as assumed in all comfort houses across China, strict rules were displayed prominently to regular soldier behavior, less in consideration of their victims but to enforce military discipline:

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply