Stranded in Shanghai I

- By Guest blogger

- 11 January, 2015

- No Comments

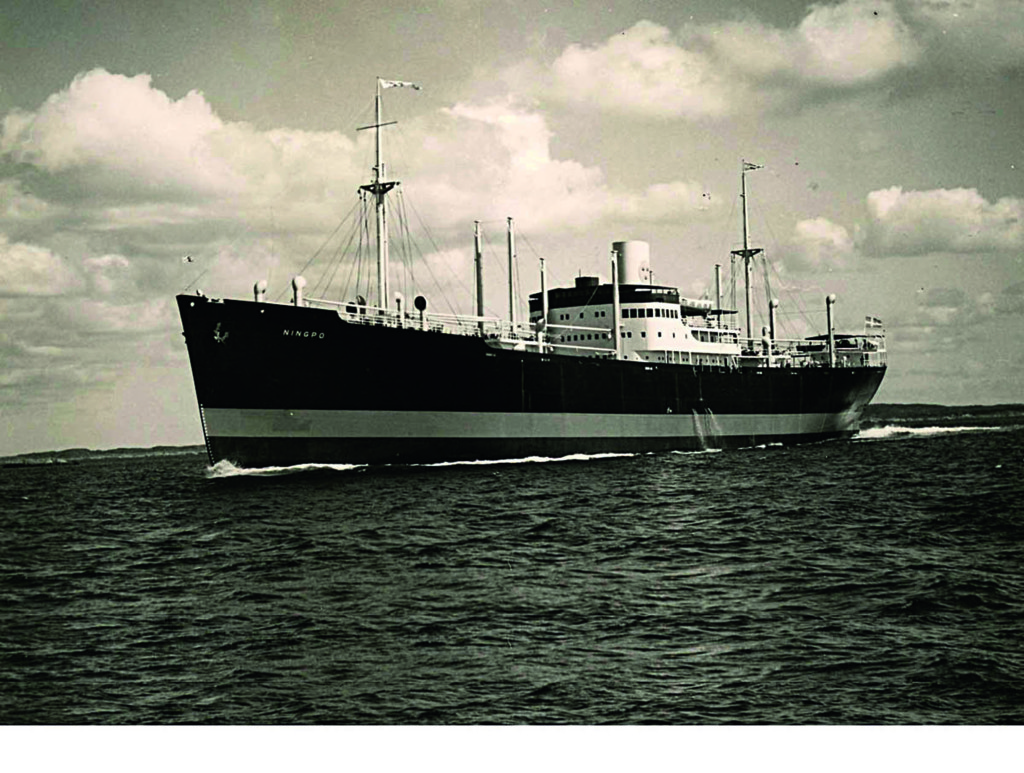

The Second World War uprooted lives across the globe, including in nations that were not directly involved in the conflict. One example was the sailor Sten Nilsson, who was born in a small town in southern Sweden in 1920 and had entered the merchant marine to see the world but  ended up being cut off from home for nearly six years. After Germany occupied his country’s western neighbors Norway and Denmark in April 1940, he was unable to return to Sweden and instead joined the crew of the Swedish ship M/S Ningpo while it was anchored in California, ready to ply the trade routes of East Asia. Nilsson is top left in the Ningpo crew picture above. Here is first part in a two-part series on Nilsson’s dramatic story.

ended up being cut off from home for nearly six years. After Germany occupied his country’s western neighbors Norway and Denmark in April 1940, he was unable to return to Sweden and instead joined the crew of the Swedish ship M/S Ningpo while it was anchored in California, ready to ply the trade routes of East Asia. Nilsson is top left in the Ningpo crew picture above. Here is first part in a two-part series on Nilsson’s dramatic story.

[The article, written by Johan G. Rystad, was first published in issue no. 6 (2014) of the Swedish magazine Svenska Öden & Äventyr (Swedish Fates and Adventures, see photo to the right), and is reproduced here with its kind permission. To visit the site of this great publication, click here. For the Swedish original of the complete story, click here]

The initial period in the Far East was fairly undramatic for Sten and his fellow sailors. There was the usual toil onboard when Ningpo transported goods back and forth among the various harbors. In the beginning of June 1941, he was in the port of Singapore when the area was hit by a violent typhoon which destroyed large parts of the harbor. In the wake of the typhoon, several mines were torn loose, and one of these drifted into the fully loaded Ningpo, which was seriously damaged in the powerful explosion. The propeller shaft and the steering mechanism were disabled, but luckily everyone on board survived.

The vessel received makeshift repairs before being towed to Manila, where it was unloaded. Later it was towed onwards all the way to Hong Kong, where it was to be repaired in the docks.

Sten Nilsson

It turned out to be a difficult journey. Towing a ship in open sea through monsoon rains and typhoon winds strong enough to capsize it was not an experience many of them had had before, and few would like to repeat. When the vessel and its crew eventually arrived at their destination, Sten and his colleagues could finally breathe a sign of relief.

While the vessel docked in the Kowloon shipyard, Sten Nilsson made himself comfortable at YMCA in Salisbury Road in Hong Kong, which was under British rule then. While waiting for the ship to be repaired, the crew was able to acquaint themselves with the bustling city and its many temptations. Life seemed good…

However, history was going to take a new turn.

On December 7, 1941 Japanese planes raided Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and also bombed the British colony Hong Kong. This was the beginning of four years of hardship for the Swedish crew from Ningpo. Just a few days after the attack, the British authorities ordered that the vessel be sunk. They were afraid it would end up in Japanese hands and become a part of their war machine. The British side outlined two very clear alternatives: Either the Ningpo was towed out into open sea and scuttled, or the Englishmen would assist with a torpedo in a strategic spot.

The ship’s officers chose the former option. On December 11, the Ningpo was scuttled in shallow water, and parts of the vessel were still visible above the water line after it settled on the bottom. Eventually, the Japanese did exactly what the British side had feared. They salvaged the ship, rechristened her Nippo Maru and put her to use for some time until she met her final destiny in 1944 when she was torpedoed by an American submarine off the coast of (the Dutch East Indies, or what later became) Indonesia.

The Ningpo

Sten Nilsson and his co-workers signed off from the scuttled ship, and by Christmas 1941, the Japanese had taken all of Hong Kong. Since they no longer received a salary, they were forced to live off handouts from the Swedish consulate. They had to find lodgings as best they could and try to keep a low profile vis-à-vis the extremely brutal occupying power. Maltreatment and executions became the new order of the day, and even though the Swedish sailors were not treated as badly as the Chinese population, every day became a struggle for survival.

Housing was crowded and miserable, but three of the officers were offered better lodgings in a house where they were put up in somewhat better conditions. In return their job was to keep an eye on the Chinese who worked in the house. Their relative comfort turned out to have a very high price. In the Easter of 1942 all three were killed in a burglary of the house.

They day after, Sten Nilsson and his 26 surviving fellow sailors were put on board a Japanese ship headed for Shanghai.

(To be continued)

Copyright © 2024

Copyright © 2024

Leave a Reply