A Social and Visual History of the Dadao: China’s ‘Military Big-Saber’ (I)

- By Guest blogger

- 12 July, 2014

- 4 Comments

Author and scholar Ben Judkins describes the Dadao, or ‘big saber’, which, despite the pre-modern technology used, played an important role in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and in Chinese military history in the 20th century more generally, in addition to having a long afterlife in popular culture. But the role and legacy of the legendary weapon are more complex than usually recognized, as he argues in this article first published on his blog Kung Fu Tea. This is the first of two installments.

Author and scholar Ben Judkins describes the Dadao, or ‘big saber’, which, despite the pre-modern technology used, played an important role in the Second Sino-Japanese War, and in Chinese military history in the 20th century more generally, in addition to having a long afterlife in popular culture. But the role and legacy of the legendary weapon are more complex than usually recognized, as he argues in this article first published on his blog Kung Fu Tea. This is the first of two installments.

Rediscovering the Dadao: A Forgotten Legacy of the Chinese Martial Arts.

Any review of the history of the Chinese martial arts in the 20th century will quickly suggest that these civilian art forms have, at various points, been co-opted and used to advance the aims of the state. Both the Nationalist (GMD) “Guoshu” program and the later Communist (CCP) “Wushu” movement sought to use the martial arts to strengthen the people, improve public health and build a sense of nationalism. However, these movements have also had a darker side. In times of conflict both national and local leaders have used them to militarize the population, supporting paramilitary organizations and guerrilla forces. These activities were widespread during both Second Sino-Japanese War (WWII from an American perspective) and the long running Chinese Civil War. Some martial arts schools, such as the Foshan Hung Sing Association (which was closely aligned with the CCP during the 1920s and 1930s) continue to promote and glorify these stories today.

Nowhere is the association between the martial arts and the militarization of the population more evident than in the creation of “Dadao Teams” between the 1920s and the 1940s. Receiving a contract to train one of these organizations on behalf of a political party, or other organization, was a major source of pride and an important form of economic patronage for civilian martial artists. In southern China (my own geographic area of expertise) leaders in the Hung Gar, Choy Li Fut and Pakmei styles (among others) were all actively engaged in training of citizen militias which were subsequently embroiled in a number of conflicts.

It goes without saying that a truly effective militia would have to be armed with modern rifles. However, the weapon that most captured the public’s imagination, becoming the defacto symbol of the paramilitary organization during this period, was the Dadao. This blade caught the mood of the country for many reasons. It harkened back to a romanticized view of the past, and it advertised the “martial skill” and attainment of the one who could wield it. It was a visually impressive weapon and had a long association with the less pleasant aspects of Chinese law enforcement. In fact, the Dadao was often an implement of terror.

This is the critical aspect of this weapon that is so often overlooked by modern martial artists with romantic notions about the past. Individuals often wonder why Chinese troops were issued a cumbersome bladed weapon as late as the 1930s. Surely this would be ineffective against Japanese machine guns and artillery?

China’s military officers were often poorly equipped and stretched to the limit, but they were not stupid. They realized that the Dadao would have limited value on the modern battlefield. Yet much of China’s brutal civil war revolved around capturing, controlling and projecting authority into villages and urban areas. The Dadao proved to be an effective means of producing terror, and therefore compliance, within the civilian population.

The weapon had another advantage as well. It could be produced very cheaply in almost any small shop or forge in the country. China was certainly capable of producing modern weapons (though admittedly their quality was variable). But it was still cheaper to arm the home guards, militias and second line troops with traditional weapons such as the spear and the Dadao. These troops often receive the rudimentary training they needed from local martial artists, and while they were not effective on the battlefield, they could be a useful resource when it came to the more mundane tasks of maintaining order and dealing with traitors. It was these two factors, the cheapness of the Dadao as a second line weapon, and the terror that it inspired as a tool of public control, that ensured the weapon’s survival well into the mid-20th century.

Currently the Dadao is enjoying something of a revival among students of the Chinese martial arts. The growing sense of nationalism within mainland China, and increased curiosity about history in the West, are conspiring to bring the Dadao back into the training hall after a nearly half century absence. The recent uptick in the popularity of “realistic” weapons training also seems to be accelerating this general trend. Further, it was so popular in the 1920s and 1930s that there are many different styles of use just waiting to be “discovered” and reconstructed.

Both practical and historical students of the Chinese martial arts might benefit from a brief description of these weapons as they actually existed and were used from the closing years of the Qing dynasty through the end of WWII. We are also fortunate in that this period is extensively documented. This provides us with the sorts of photographs and accounts that students of earlier periods of martial history can only wish for. All of this makes the sudden rise and fall of the Dadao a good case study for change and adaptation within the Chinese martial arts more generally.

One could easily write a book on the Dadao and what it reveals about the evolution of the Chinese martial arts and their ever evolving relationship with society. Clearly such a project is beyond the scope of this article. Instead I hope to use a number of historically important pictures to suggest the basic outline of this story. A more comprehensive treatment will have to wait for a later date.

However, there are number of outstanding issues that must be addressed before we can undertake even a brief review. First, there is little consensus as to how to best translate “Dadao” into English. The character used for “Da” means “big” or “large.” “Dao” translates to “single edged knife.” Unfortunately “Dao” does not imply anything about the length of the knife in question or its intended purpose. A paring knife or a cavalry saber can both be referred to with this same term in Chinese.

This causes confusion when students of the Chinese martial arts speak in English with non-specialists. They are often adamant that a Chinese military saber should be called a “knife”, which is technically correct in Chinese, but is absurd in English. A literal translation for Dadao would be “big knife.” Yet when talking about a weapon that might be three feet long and requires two hands to wield, such a rendering seems calculated to cause confusion.

Some martial arts teachers refer to the Dadao as the “military machete.” While this does not attempt to be an exact translation of anything it does provide the reader with a basic visual image of what is being discussed. The broad blade of the Dadao does (to some degree) resemble the short broad blade of a jungle machete. It is also the sort of tool that one might expect military troops to carry.

Still, there are problems with this translation. It implies that the Dadao might be a tool with some sort of practical application. I suspect that this is mistaken. I have never run across an account that indicates that these weapons were useful “camp tools” in the same way that a kukri or a machete might be. The Dadao is a purpose-built chopper. The blade of the machete is thin and flat to cut vegetation without resistance. Most Dadaos have a much heavier blade with a triangular profile. They are really only good for hacking through flesh and bone. The heft of the weapon is distinctively ax-like.

For all of these reasons I favor translating Dadao as the “military big-saber.” This should be enough to convey that we are dealing with a single edged weapon that differs from other, more conventional sabers. It also has the added advantage of being a somewhat popular solution to our linguistic quandary.

Our second problem has to do with the photos below. I gathered most of these off the internet and while I have spent a couple of hours trying to figure out where they were originally published, that has not always been possible. The circular republication of vintage material with no attribution of its ultimate origin is a problem in a lot of the Chinese language literature on the martial arts. If any reader has firm information about the origins of an unlabeled photo, please let me know in the comments. I am currently trying to collect this information.

Origins of the Dadao

Our first puzzle has to do with the early development and adoption of the Dadao. While 20th century examples of these weapons are quite common, very few examples can be reliably dated to the early Qing dynasty. This is odd as Qing military regulations dictated that a number of these swords should be issued to every unit, but evidently they did not survive in great numbers. Occasionally weapons turn up on the antique market with very early dates or are even attributed to the “Ming era.” Great caution is required as few swords from the Ming period have survived at all and I don’t think I have ever seen a Military Big-Saber that dates to this period.

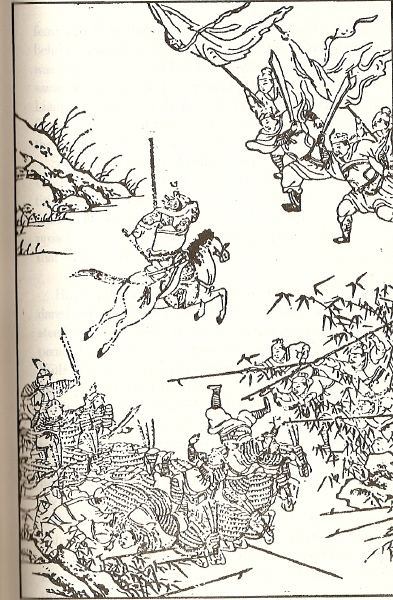

Still, one school of thought basically holds that the modern 20th century Dadao is a resurrection, or a re-imagination, of a classic Ming era weapon. While similar weapons seem to have become less fashionable during the early Qing (though regulations did exist for its use in the army), stories of the Ming dynasty and the exploits of its heroes became quite popular in the 19th century. When republished these stories were often illustrated with copies of Ming era illustrations, or with new images of heroes dressed in Ming style cloths with antique weapons. Their swords often featured ring shaped pommels and clip point blades. In fact, many of the same fashion styles were preserved in both Mandarin and Cantonese theater companies so people were fairly familiar with them.

A Ming era publication that shows images of Dadao like swords. Images of these swords were probably popular in period publications because of their dramatic blades.

The end result of all of this is that the image and the lore of the Dadao was easily available for anyone seeking to resurrect the glory days of China’s martial past. It was occasionally seen in the official military, and it was often featured in stories and popular fiction. Further, the simple blade and ring pommel design would have been fairly easy to produce compared to the more complex dao’s of the mid-Qing. Such swords were often favored by the various “Big Sword” militia groups that became increasingly common from the end to the Taiping Rebellion onward. The arms of these groups carried romantic associations with the past and often included the ringed pommels. However, they featured a wide variety of blade types from long sabers to short heavy choppers. While the idea of the “Big Sword” was a common symbol in 19th peasant militias, I haven’t seen much evidence to indicate that they standardized on any one weapon in particular.

A second theory is that the modern Dadao actually has little to do with its ancient predecessors or weapons used by the Imperial military. There is at least some evidence to support the assertion that a Dadao is basically an enlarged and modified farm tool. This would hardly be the first time that a farm implement found its way onto the battlefield. The Nepalese kukri was an agricultural tool long before it was used by the British Gurkha’s in WWI. It might also help to explain why Chinese smiths often made the blades of the Dadao shorter than one might expect for a weapon. They may have had some other pattern in mind when doing their work.

If you look at antique farm implements, or even wander around a traditional food market in Hong Kong or Shanghai, you will see lots of chopping knives that look like scaled down versions of a Dadao. Often these seem to be favored by vendors selling tough skinned fruits or vegetables. Butchers simply use the traditional cleaver. Still, while similar in shape and function, there is a world of difference between the Dadao and a “watermelon knife.”

A third suggestion that I have seen offered is that the Qing era civilian Dadao is really a modified pole weapon. The Chinese military traditionally employed a number of pole-mounted choppers, and the blades of these weapons resemble the basic size and profile of a Dadao. The type of riveted handle seen on many Dadaos is also very similar to the long riveted tang that is preferred in the construction of large heavy choppers. The handles of normal sabers or “Daos” are peaned in place, rather than riveted.

This theory may have something to it. In antique auctions I have personally seen Dadaos constructed from much older pole mounted choppers whose shafts had been lost or broken. This sort of recycling was pretty common on the “Rivers and Lakes” of China. Further, for reasons that we will explore below, there are no standard measurements for what a “regulation” Dadao must be. This is not say that various self-appointed experts did not have opinions on the matter. They certainly did. Yet seems that few manufactures were actually listening all that closely. For instance, some examples being made up through the mid 20th century continued to have very long handles. It is not always clear whether a given weapon should be classified as a Dadao (Military Big-Saber) or Pudao (Horse Cutting Knife).

At the moment I do not feel that there is enough evidence to speak decisively on the evolution of the Dadao and its subsequent adoption by civilian martial artists. What we do know is that the coming of the Qing Imperial army privileged the conventional saber as it could be used from horseback whereas the two handed Dadao is strictly an infantry weapon. While the heavy chopper seems to have faded from public consciousness it never totally disappeared and it’s popularity among civilian martial artists, bandits, guards and paramilitary organizations exploded during the final decades of the 19th century. This resurgence in popularity was further boosted in the 1920s and 1930s.

These groups were likely attracted to the Dadao for three reasons. First it provided a visual connection to the romanticized Ming dynasty. Second, it was a simple weapon that could be produced practically anywhere. Lastly, being a double handed weapon individuals who had grown up using farm tools (and that was pretty much everyone in China) could master it relatively quickly. What it lacked in range or sophistication it made up for with its immense slashing and chopping power.

The Dadao as an Instrument of Police Control in Late Imperial and Republican China.

Modern researchers and collectors are fortunate in that we have copies of the official regulations governing weapons bought by the Qing government for the imperial armies.

While the single handed saber was clearly the preferred weapon, enough period choppers survive to attest their use in the Qing army. These weapons came in two official varieties. The “kuanren dadao” is a very large weapon, more on the scale of a horse knife. The Qing-era “chuanweidao” is smaller and shows more similarities to the modern Dadao.

Period photographs give us a good visual record of how these swords were actually being used by the end of the Qing dynasty. Not many photos of Qing era troops armed with any sort of sword at all survive from the final decades of the dynasty. From the end of the Taiping rebellion on, all main-line Qing troops had modern rifles. By the time of the Boxer Uprising they also had modern machine guns and artillery. Officers continued to carry swords, but increasingly even these followed European patterns.

The one place where the Dadao really seems to have survived was in law enforcement. Specifically, public executions and beheadings were often carried out with the dadao or some sort of similar, often very short, chopping blade.

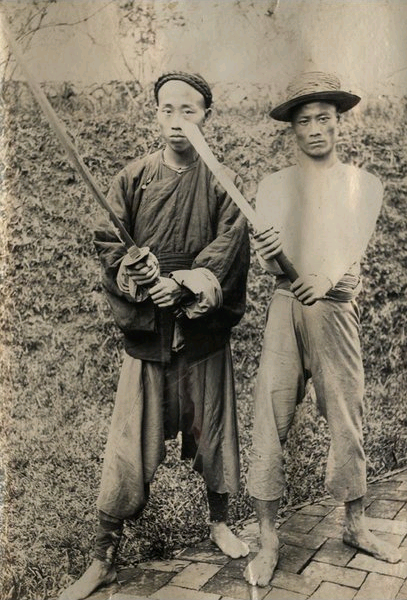

The picture below records two executioners displaying their weapons prior to the public beheading of the perpetrators of the 1895 “Kucheng Massacre.” This is an important photo for a number of reasons. To begin with it has a clear provenance and is linked to specific, date, place and historical incident.

Executioners of the perpetrators of the Kucheng Massacre, 1895. USC Digital Collections.

The weapons being displayed are also quite interesting. The gentleman on the left has what appears to be a fine Japanese Tachi. Note that the flash from the camera has illuminated a section of active hamon at the base of the blade. One can only wonder how this sword ended up in the arsenal of the local yamen. It is a good reminder that the Chinese have been very interested in Japanese swords since at least the Ming.

The other executioner carries a short, heavy bladed chopper. It has a simple guard and the handle, almost as long as the blade, is wrapped in cotton cloth (probably colored red). The blade looks too small for its intended task, yet execution swords were often not much longer than this.

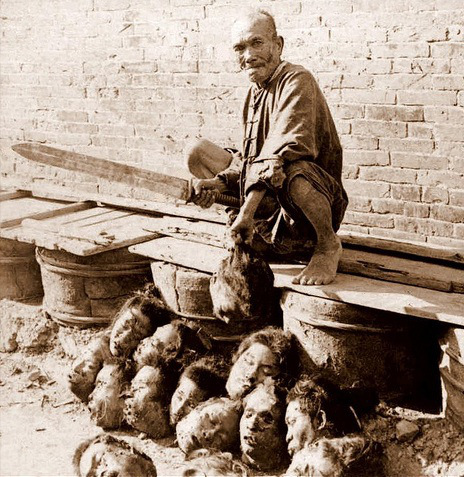

An executioner displaying a pile of heads along with his weapon. Note that the sword is a short heavy “jian” (double edged sword) rather than a Dadao. It should be remembered that executions were carried out with a variety of tools. Very often these are shorter than one would expect, but apparently that did not impede their efficiency. This particular photo probably dates to the 1920s and was published on period ephemera. It can sometimes be found on vintage postcards and stereoscope slides.

The Dadao was also seen in urban police and law enforcement units. Chinese governments worked hard to establish modern law enforcement in the major urban areas between 1900 and 1930. Some of these reform efforts drew on western ideas of “scientific” criminology and law enforcement, others did not. Very often 3-4 different types of law enforcement might be operating in a major city at one time. For instance, there might be a model western style police force under the control of one office, a group of plain cloths detectives (who were expected to be close to, or even part of, the criminal underground) who answered to a different office and lastly there were usually patrols of military police to maintain “public order” in the street. In cities such as Shanghai the situation could be even more complex.

A Qing era police patrol. Note the mix of both modern rifles and a Dadao, used for executions. This photo was a popular subject for reproduction and can sometimes be found on vintage postcards

For much of the early 20th century it was the “military police” that one would most likely see in public spaces. Under both the Qing and Republic governments these individuals were normally regular infantry soldiers who were assigned to the task. Often soldiers from a different part of China were chosen to be law enforcement officers as it was thought (usually incorrectly) that linguistic difficulties and regional animosities would make them less susceptible to local corruption.

These police officers would generally travel in small groups of between 4-6 individuals. They might include an officer or a Sargent who acted as the leader, 2-3 individuals who could apprehend criminals, and an executioner. Individuals who were caught stealing or causing disorder in the market place would be apprehended, bound and usually beheaded in the middle of the street after a very brief “trial.”

It is important to realize that early 20th century China was a highly volatile place. The government, whether run by the Qing, the Republic or individual Warlords, attempted to keep the population in check through what amounted to a continuing campaign of public terror. This is how the Dadao was first seen by most of China’s citizens. It was the living embodiment of the state’s monopoly on legitimate violence.

Nationalist soldier executing a member of the Guangzhou Commune, 1927.

Dadaos in the Republic of China and Warlord armies of the 1920s-1930s.

One cannot underestimate how strong these symbols are or how deeply engrained they become in the public psyche. The situation in China was complicated by the fact that large parts of the nation’s leadership and population did not agree on who held actual political authority and the rights to exercise public violence that went with it. As a result Nationalist (GMD) revolutionaries were quick to adopt the Dadao as a tool of public law and order after they succeeded the Qing. They too employed military police and the display of the Dadao left the public in no doubt as to who could claim rightful control of the state.

An early image of an unknown group of soldiers, all armed with very long handled Dadaos. Probably 1920s.

Nor were they the only group to realize the political utility in the Dadao. Bandit gangs and armies in the central plains and western China had long valued the Dadao for its more practical attributes. As these gangs were gathered into the various “Warlord Armies” they took the Dadao with them. Even though they were now armed with rifles, handguns and grenades, the Dadao remained a powerful symbol of both the personal and corporate “will to power.”

Member of a northern Warlord Army displays his Mauser handgun and Dadao. This picture probably dates to the 1920s.

A commonly republished photo showing nationalist soldiers in ranks all carrying Dadaos. Date unknown, probably 1930s.

It is worth remembering that a variety of blades were carried by Chinese troops between 1920 and 1945. Not even all “Big Sword” units were issued Dadao. This photograph shows the 8th March Army displaying a different style of double handed saber in 1933.

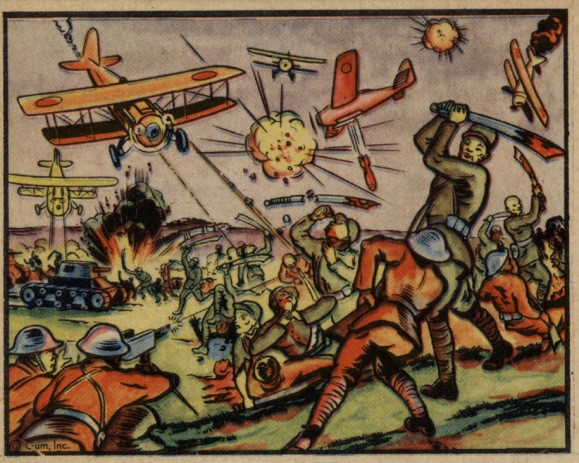

It was the soldiers of these western armies that would bring the Dadao to the attention of the wider world through their desperate attempts to defend the Great Wall against Japanese advances in 1933, and then the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident” where they defeated a superior Japanese force using a Dadao charge in 1937. In their hands the Dadao became a dual symbol to the outside world. It represented the fact that the Chinese people were willing to fight for their own freedom (something that was often doubted in the West), but it also encapsulated and reinforced nearly a century’s worth of fears and prejudices. The personal nature of this weapon seemed to suggest that the Chinese reveled in violence and brutality, and were still “less than civilized.” In China public executions and the Dadao acted as a twin symbolic code for “political authority” and “legitimacy.” Unfortunately these symbols did not translate well in the more liberal west.

An American trading card from the 1938 “Horrors of War” series. This image was labeled “Chinese ‘Big Sword’ Corps Resist the Japanese.” Author’s personal collection.

The domestic situation in China was different. If anything the importance of the Dadao as both a practical and symbolic weapon increased as the 1920s turned to the 1930s. After the rupture with the Nationalist Party (GMD), and the subsequent outbreak of violence with the Japanese, the CCP began to form larger militia units. These groups were expected to both fight the GMD and the Japanese, as well as to pacify and hold segments of the country side. Once again, the Dadao was a featured weapon in their arsenal.

Other paramilitary groups, such as railway police units, were also quick to adopt the Dadao during this period. As a matter of fact, it is among these other troops that the Dadao is most commonly encountered. I have looked through enough photos of military units during the Republic of China period to conclude that the Dadao was actually rarely encountered among front-line infantry troops. While there certainly were “Big Sword Teams” within the main body of the Nationalist Army, they were an exception rather than the rule. Most often such swords are seen in the hands of special forces troops, military police, local militia, paramilitary revolutionaries and railway guards. All of these groups were more likely to deal with the domestic population than the Japanese.

One of the most famous images of a Chinese soldier with a Dadao. Originally published as a postcard, the individual in this image is actually a railway guard.

(To be continued.)

© Ben Judkins. No part of this article may be reproduced without the author’s prior permission.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

The execution picture is not of nationalist era but one from late Qing period. Judging from the padded clothing it would more likely be in northern China. That particular photo also appeared to have been photoshopped.

And I think you mean “Marco Polo Bridge Incident”.

I’ve seen that pic in a book that was published before I was born in 1970. I still have that book. It says the execution was in the 1920s. And if the picture has been doctored, it’s not by Photoshop.

Although antique military swords and weapons were the only weapon of survival used in civil war yet today it has not lost its grace. Many companies have contribute to military army for supplying swords and they are now supplying to antique collectors as well. They use them for decorating their houses and keep them in museums.

You can correctly translate Dadao as Chinese Scimitar, Dadao shape is more similar to Scimitar than to Saber.