‘Ningbo Special’

- By Peter Harmsen

- 24 May, 2014

- No Comments

In the early afternoon of August 16, 1937, six Curtis Hawk III aircraft from the 25th Squadron of the Chinese Air Force took off from their base in East China, heading for Shanghai. China’s largest city was quickly becoming the main battlefield in the war with the Japanese invader, and the Chinese Air Force was playing a decisive role in an all-out effort to secure a quick victory before the adversary could send in reinforcements and turn the tide.

In the early afternoon of August 16, 1937, six Curtis Hawk III aircraft from the 25th Squadron of the Chinese Air Force took off from their base in East China, heading for Shanghai. China’s largest city was quickly becoming the main battlefield in the war with the Japanese invader, and the Chinese Air Force was playing a decisive role in an all-out effort to secure a quick victory before the adversary could send in reinforcements and turn the tide.

At 3:15 pm, the six planes, led by Captain Dong Mingde, began their attack on positions held by Japanese Marines in the north of the city, heavily outnumbered on the ground. Five of the planes released their bombs and made a successful return to base. The sixth, Curtis Hawk No. 2503, also known as “Ningbo Special”, was not so lucky. The plane’s fuel tank was hit, and the pilot, only known by his surname Zhang, was forced to make a landing at the Far East Stadium, well south of the Japanese positions. This gave him a headstart, and before Japanese soldiers caught up with him, he was able to escape, helped by Chinese civilians.

Exactly what brought the plane down depends on who you believe: According to Chinese sources, it was the victim of an accidental lucky shot by a Japanese anti-aircraft gun. The Japanese side offered a version more flattering to itself, saying that it was shot down by a Kawasaki Ki-10 biplane from aircraft carrier Ryujo, anchored off Shanghai.

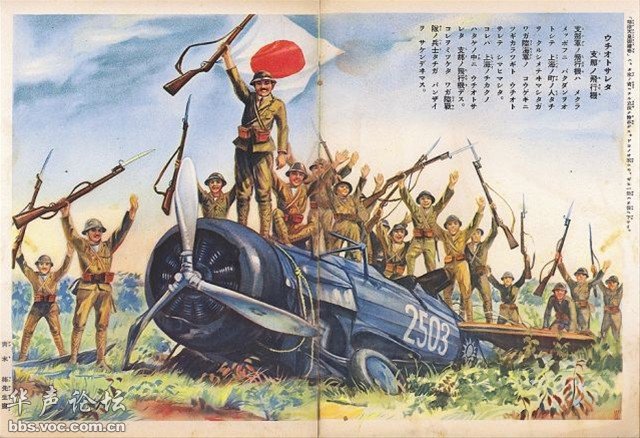

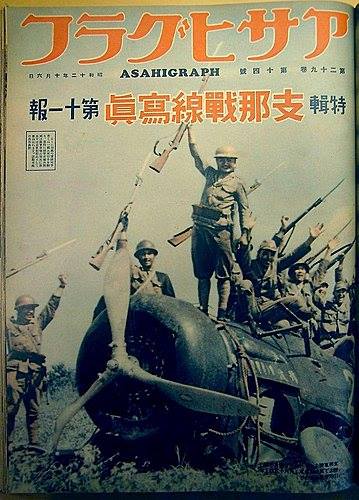

Either way, it was a propaganda triumph for the Japanese, and they made sure to exploit it to maximum effect. In the ensuing days and weeks, it probably became the most photographed aircraft of the entire Shanghai battle, as Japanese soldiers posed heroically on top of the wreckage for the benefit of the press. Later it was taken back to Tokyo and put on display there, along with other trophies.

Either way, it was a propaganda triumph for the Japanese, and they made sure to exploit it to maximum effect. In the ensuing days and weeks, it probably became the most photographed aircraft of the entire Shanghai battle, as Japanese soldiers posed heroically on top of the wreckage for the benefit of the press. Later it was taken back to Tokyo and put on display there, along with other trophies.

The “Ningbo Special”, probably named so because it had been bought with donations from the citizens of the Chinese city of Ningbo, had a long afterlife in Japanese war iconography. It even became a motif in a book for children about the war in China. That’s the image at the top. Below other examples from the media in the second half of 1937.

Two Japanese officers study British-built Vickers Mark E tank captured from Chinese in Shanghai. The No. 2503 in the background

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply