Mon Dieu! The Fate of a French Port in China

- By Guest blogger

- 16 November, 2016

- 2 Comments

The Allied victory in the war in Asia in 1945 meant the end of not just Japanese imperialism in the region, but also, paradoxically, European imperialism. An example of this is the fate of a French treaty port in south China in 1945. This article is part of a large online project — End of Empire — launched by the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies (NIAS). The idea is simple: To describe day by day the 100 days immediately after Hiroshima. This article, Geoffrey Gunn is Emeritus Professor, Nagasaki University, is reproduced with the kind permission of NIAS. Check out End of Empire here or the Facebook page here. The entire project has now also appeared in book form, see here.

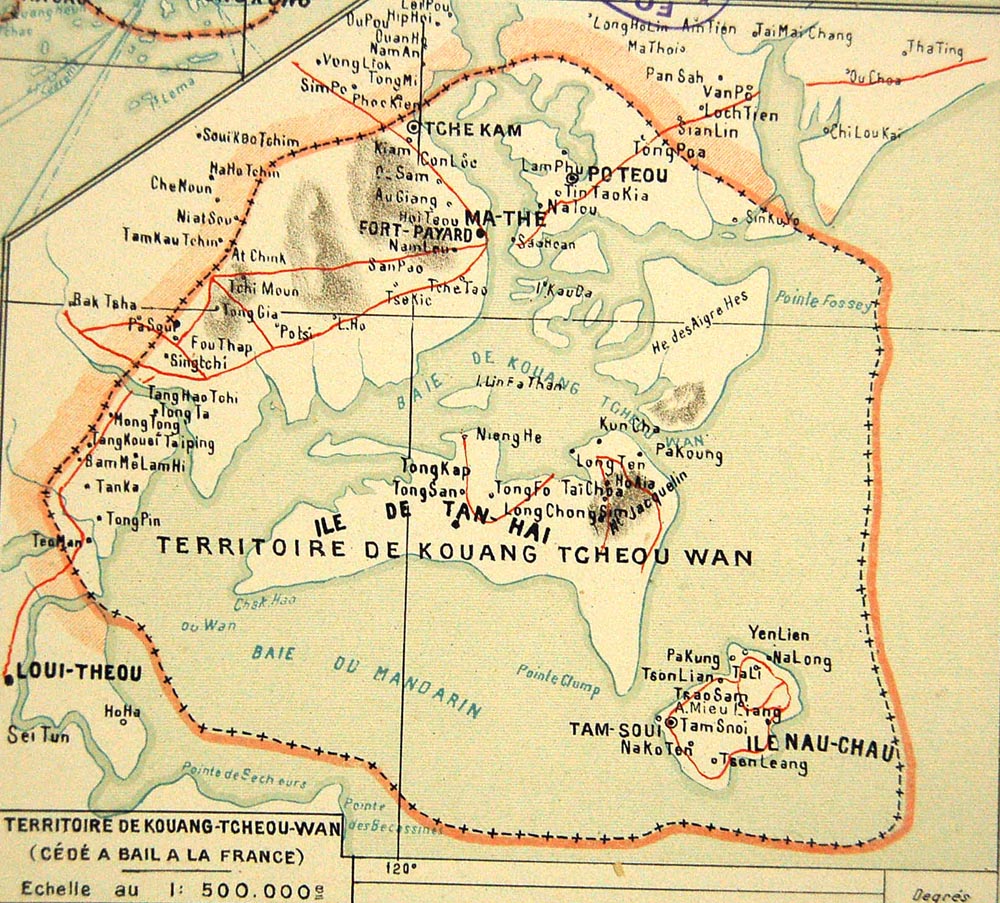

It is somewhat ironic that France never regained postwar control over KouangTchéou-Wan (Kwang-Chou-Wan), now known as Guangzhouwan. France leased the territory on the Luichow Peninsula in southern Canton (Guangdong) province through the Sino–French Treaty of 15 November 1899. In 1945, Chinese Nationalist forces accepted the surrender of Japanese troops in Kouang-TchéouWan and, as with numerous other treaty ports, leased territories and concessions where Britain, France, the United States and several other countries had specific rights, Chiang Kai-shek had no intention of facilitating the status quo ante.

Japan’s intentions were also clear. On 15–16 February 1943, some 500–600 Japanese invaded Kouang-Tchéou-Wan with its strategic harbour and protected bay astride the sea route between Taiwan, Hainan and French Indochina, albeit leaving Vichy France in charge (see photo above). This action prompted the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs to lodge a protest to the Free French Legation in Chungking over violation of the Sino–French Treaty, notably the clause stipulating that Chinese sovereignty over the territory was not affected by the lease and that China was no longer bound by that Treaty. On this occasion, and contrary to Chungking’s interests, Tokyo exhorted Vichy to give up all concessions and extraterritorial rights in China, including interests in Shanghai, Amoy and the Legation Quarter in Peiping, citing pressure from the puppet government in Nanking. Needless to say, the Free French government of Charles de Gaulle did not recognize this capitulation agreement. In any case, in the wake of Pearl Harbor, Japanese occupation forces virtually moved in upon remaining foreign concessions in China. Even Japan’s Axis partners were not spared, with Mussolini’s Italy pressured over its concession in Tienstin.

On 10 March 1945, simultaneous with Operation Meigo in Indochina and action against the French concession in Shanghai, Japanese troops invaded and occupied the French administrative center of Fort Bayard (Zhanjiang), disarming the French military but allowing most French civilians to remain free. On 18 July 1945, taking actions into their own hands, local pro-Nanking government forces effected what French intelligence described as a ‘virtual preemptive coup’ in favour of the puppet regime. With two or three exceptions, all French nationals were arrested and interned in the Banque de l’Indo-chine. Held incommunicado, only their children were allowed outside. Food was rough riz rouge. To the surprise of the French, local strongman Tsang Hoc-tam then emerged as Kouang-Tchéou-Wan’s puppet administrator. Honoured with a Légion d’Honneur, he had hitherto maintained excellent relations with the Vichy regime. Even following the Japanese coup of 10 March, he was regarded as Kouang-Tchéou-Wan’s most prominent Chinese individual. Commanding enormous wealth derived from his ownership of lucrative opium and gaming monopolies, Tsang was also known to have paid off the Nanking puppet government and local Japanese gendarmerie, as well as Chungking agents. He kept law and order in Kouang-Tchéou-Wan with his own private army, also suggesting the emergence of a local strongman in the absence of credible overarching authority.

With the Japanese still in control in Kouang-Tchéou-Wan, representatives of the Provisional French Government and the Chinese Nationalist government, meeting in Chungking on 18 August 1945, signed a retrocession agreement sealing the fate of the territory. Beginning with an exchange of letters on 13 May 1945, it was actually the Chinese side that accepted the French proposals on the basis that retrocession was an exercise of diplomacy and not force. Article I declared the November 1899 Convention to be abrogated and that all rights accorded France by the convention would expire. Article II set forth the modalities of the return of the territory to Chinese sovereignty (along with all buildings and archives including land documents). Under Article V, China agreed to offer a 30-year renewable lease to France of its official residence to serve as the seat of a future French consulate, if the offer was taken up within a year. (In the event, France did not exercise this right.) Article VI indicated that the convention would take effect immediately. At Chinese insistence, a seventh article was added stipulating that the Treaty be established in both French and Chinese languages with the two versions having equal validity. With the departure of Japanese forces in late September, representatives of the French and Nationalist Chinese governments proceeded with the transfer of authority. The tricolor was lowered for the last time on 20 November 1945.

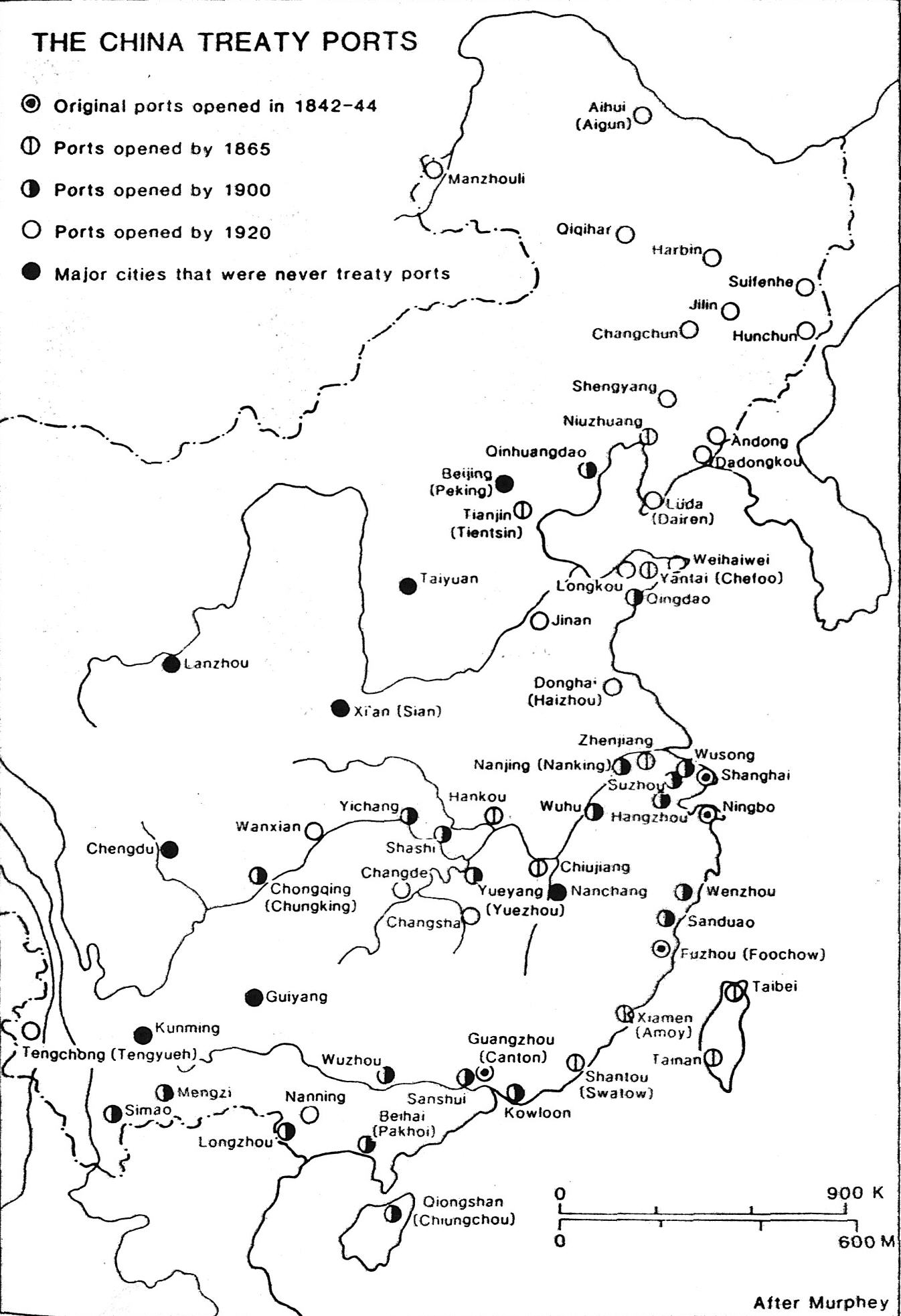

With the obvious exception of Hong Kong (reoccupied by the British) and the exceptional case of Portuguese Macao, the retrocession of all treaty ports and concessions followed a similar process. Although the British and Americans had entered into wartime agreements with the Chiang Kai-shek government in February 1943 as to the relinquishment of extra-territorial rights in China, and both sides worked together to foster a smooth transition, the changes were unenforceable until the end of the war. By 1946, UK, French and U.S. interests in the Shanghai International Settlement would be abolished. In turn, Britain lost its concessions in Canton (Shameen), Amoy and Tientsin, as did Italy in Tientsin in 1947. The Japanese concessions in Tientsin, Hankow and elsewhere in China also ceased to exist with the capitulation in 1945. Under the 28 February 1946 Sino–French Accords, France formally relinquished extraterritorial rights in Shanghai, Tientsin, Hangkou and Shameen, and pledged that Haiphong would be a free port for Chinese. The conciliatory mood on the part of France in these negotiations can in large part be explained in the context of discussions with the fledgling Democratic Republic of Vietnam, and the pressing question of the exit of Chinese Nationalist occupation forces from Indochina.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Superb blog you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any

message boards that cover the same topics talked about here?

I’d really love to be a part of group where I can get opinions from other knowledgeable individuals that share the

same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know.

Thanks!

I was wondering if anyone had information regarding the US operation that entered Fort Bayard during the last days of the war. Their original mission was to obtain information for assault landings at Fort Bayard. However, with the surrender of Japan imminent, their mission was changed to enter the town and secure the safety and well being of the French POW’s and civilian internees located there.