Operation Chahar, Part 1

- By Guest blogger

- 30 January, 2016

- No Comments

The Nankou Campaign, sometimes known as “Operation Chahar,” broke out on August 8, 1937, that was 5 days earlier than the outbreak of the famous Shanghai Campaign. For decades, the Nankou Campaign has been concealed in oblivion. This article, written by Eric Wu, provides a summary of the chronology and focuses on the meaning of this campaign based on the study of many primary sources. This paper argues that the Chinese Army did not suffer an absolute defeat based on the comparison between the casualties of the Nankou Campaign and some early battles in other theaters during the Second World War. The previous view, that China only resisted the Japanese invasion reluctantly and waited for assistance from other Allies, should be revised. This is the first part of a two-part series.

The Japanese captured Beiping and Tianjin on July 29 and 30, 1937, right after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of July 7 in the same year and attempted to push forwards into the west, especially Shanxi Province where abundant coal mines were stored underground. Controlling West China was a strategy of the Japanese invaders. They located the natural resources on a map after investigating the economic circumstances of West China.

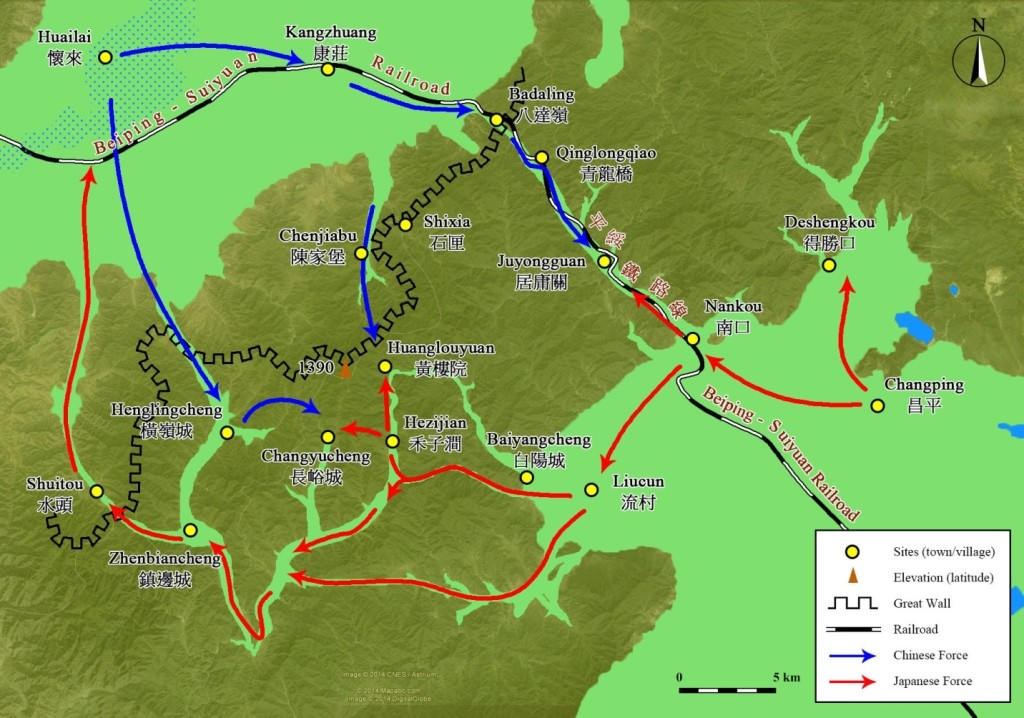

Located in the first key position along the only path heading to North-western China, Nankou, which means the gap at the southern end of the Guangou valley, has been a site of strategic importance disputed by each force in most ancient conflicts. Along this valley, three fortifications were built for defense from the south to the north: Nankou, Juyongguan and Badaling. The Beiping-Suiyuan Railroad was also built through this valley. Behind the mountains was another plain on the north-west with few natural obstacles that could prevent mechanized armed forces from deeply advancing into north-western China. This was especially important because Shanxi Province was where abundant coal supplies were stored underground. As a consequence, Nankou was a crucial strategic site for the Japanese to take since they planned to advance into Shanxi.[1]

Fig. 1 Map of the North-western China created by the Japanese Army, marked with resources and productions, 1938[2]

Having recognized the demand to access and control these strategic coal reserves for decades, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) deployed its troops of over 70,000 soldiers to attack and capture Nankou from the south-east side, out numbering the Chinese defending force. Due to the fact that the north and the east had already fallen, the Japanese intruded from the south-east, and the Chinese Army was obliged to fight alone against enemies on three sides. Obviously, it was difficult to defend the Guangou Valley and the Beiping-Suyuan Railroad. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek ordered the 7th Army Group of Chinese Revolutionary Army (NRA), directed by General Tang Enbo, to the frontier.

At the time, Liu Ruming, local governor of Chahar (Chahaer) Province, which was on the north of Beiping, was concerned about being replaced once General Tang‘s Army arrived. So he prevented Tang‘s Army from getting through his area and marching to Nankou for four days, which was a terrible loss of time and the chance to get prepared for battle.[3]

Table 1 Designation and Troops of Chinese NRA in the Nankou Campaign[4]

| Designation | Troops | Location for Battle | Date of Fighting | |

| 13th Army | 4th Division | 28,000 | Nankou, Deshengkou | August 8 -26 |

| 89th Division | Hengling | |||

| 17th Army | 21st Division | 14,000 | Juyongguan, Hengling | August 15- 26 |

| 84th Division | Ningjiangbu, Dushikou, Guandijian | August 8 -26 | ||

| 94th Division | 5,000+ | Yongning, Yanqing, Sandaoguan, Ningjiangbu | August 14 – 26 | |

| 72nd Division | 6,000 | Zhenbiancheng, Hengling | August 18 – 26 | |

| Independent 7th Brigade | 4,000 | Huailai, Bandayu | August 19 – 26 | |

| 27th Regiment (Artillery) | 2,000- | Huailai | ||

Table 2 Designation and Troops of Japanese Forces in the Nankou Campaign[5]

| Design ation | Troops | Numbers of Canon | Date of Fighting |

| Suzuki 11th Division, Sakai 1st Division | 30,000 | 40+ | Early August |

| Kawagishi 20t h Division | 10.000 | Not Clear | Middle August |

| 1tagaki 5th Division | 25,000+ | 200+ | Late August |

| Air Force and Cavalry | Unknown | ||

| Other troops for feint | Unknown |

The massive conflict in the Nankou Campaign broke out on August 8, 1937 in the Town of Nankou. Relying on the overwhelming weaponry including bombers, tanks, artillery and even toxic gas, the Japanese troops intended to eliminate all Chinese forces and capture Nankou – Juyongguan – Badaling in five days.[6]

Due to the forceful bombing from the Japanese Air Force, the Chinese reinforcements, with great difficulty, rushed to the front. As soon as they arrived at the front, they were forced to counterattack the Japanese without having their troops concentrated. As a result, the Chinese Army was fighting alone against the enemy on three sides in the Nankou Campaign.[7]

Fig. 2 the main Battlefield of the Nankou Campaign, showing the movement of the armies and locations of critical sites

The Japanese Army enjoyed the fact that they had overwhelming power. To their surprise, however, three regiments of the Chinese Army were not as weak as the Japanese had expected. These three regiments were equipped with German rifles, and actively resisted the intruders. After the Japanese fought for a week, Juyongguan was still controlled by the Chinese defense. The 89th Division of the Chinese Army held its positions around Juyongguan throughout the Campaign, though at a terrible cost of over half of its troops.

On August 16, the Japanese troops began to outflank the west of the Chinese defense, attempting to find a weak point somewhere else. Wu Shaozhou, Chief of Staff of the 89th Division, assembled parts of the 21th and 94th Divisions, rushed to Huanglouyuan[8], a stronghold along the Great Wall, and blocked the enemy. Simultaneously, the immobilized 72nd Division from Shanxi Province assisted the 4th Division to reinforce the defense at Hengling Village. The vanguard of the 72nd Division recaptured the 850 Elevation that had once fallen to the Japanese force, during which Zhang Shuzhen, the commander of the 416th Regiment, died in the battle.[9]

The Japanese failed again to break the Chinese defense until they took control of Zhangjiakou City on August 25. They breached through Shuitou, a weak point along the Great Wall on the west of Zhenbiancheng, guided by Chinese traitors. Thus, the Chinese defense at Juyongguan was almost besieged, and Juyongguan became an isolated stronghold. It became meaningless to defend the pass at Juyongguan anymore. The Chinese Army had to retreat. Complying with the order at 1:30 p.m. on August 26 by the military committee of the ROC, all Chinese troops retreated in turn and gathered at Yu County in Hebei Province.[10] So far, the NRA had gone through a military mission of one month and three days.

[1] van de Ven, Hans J. “Chapter 5: A forward policy in the north.” In War and Nationalism in China, by Hans J. van de Ven. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003, pp. 193-196.

[2] Newspaper Group, Army Ministry of Japan. Records of Achievement during the Incident of China. Tokyo: Army Consolation Bureau, 1938. 140.

[3] Wang, Zhonglian. A Brief Analysis of Strategic Theories and Actual Battles. Taipei: New Culture Press, 1987, p. 3.

[4] Gou, Jitang. “The Battles around Nankou.” Chap. 1 in Actual Battles of the Chinese 3rd Front during the War of Resistance against Japan. Taipei: Wenxing Publishing House, 1962, p. 10.

[5] Gou 1962, 7.

[6] Changping District Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultive Conference 2007, 472.

[7] Telegram, Chiang Kai-shek to Tang Enbo, August 14th, 1937. Wang 1987, 50.

[8] Gou 1962, 17.

[9] Chen, Changjie. “Fierce Battles along the Great Wall.” Chap. 3 in Recollection of the Former Nationalist Commanders’ Experience during the War of Resistance against Japan – Marco Polo Bridge Incident, by Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference Committee of Cultural and Historical Data, 166-181. Beijing: Chinese Literature and History Press, 1986, pp. 166-181.

[10] Gou 1962, 24,25.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply