Jiangyin 1937: Battle for the Yangtze, Part 2

- By Peter Harmsen

- 25 December, 2015

- No Comments

The first months of war between China and Japan in the fall of 1937 took place mostly on land and in the air. But the two nations’ navies also clashed in a fierce battle over the strategic city of Jiangyin on the Yangtze River. This is the second in a two-part series about this crucial, but forgotten episode in the history of the Second Sino-Japanese War, involving vessels such as the Japanese ones pictured above, moored in Shanghai around the time of the outbreak of hostilities.

It wasn’t until the middle of autumn that war came to Jiangyin in a serious way. The first major air raid on the First Fleet took place on September 22, a full seven weeks before the fall of Shanghai and the start of the Nanjing campaign. On that day, 30 to 40 Japanese planes swooped down over the Chinese vessels, concentrating their fire on the Pinghai, Admiral Chen’s flagship. Liu Fu, a young officer on board the cruiser saw the contours of the Japanese planes against the sky. Next he saw small black dots detach themselves from their bellies. They were bombs. “Get down!” he shouted to the sailors around him. (1)

He sensed a red flare, felt a violent jolt shake the entire body of the ship, and was knocked over by ear-splitting explosion. The Pinghai had taken a direct hit. He rose to inspect the damage when a new explosion tore into the vessel. A seriously injured gunner was leaning limply over his anti-aircraft gun. “I’m finished. I’m going to die,” he wailed. An older sailor looked at him unfeelingly. “You don’t have permission to die just yet,” he said. “Wait until the reinforcements are here.”

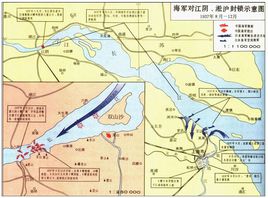

Jiangyin is located on the Yangtze, near a section where the river dramatically narrows, making it a key strategic asset.

The Japanese raids continued over the next six hours. At the end of the day, the Pinghai looked like a floating wreckage. The length of the hull was holed by enemy shrapnel, and the deck was covered with shards of broken glass, blood and gore. Chen Jiliang met with his staff at night. Some officers proposed cutting the losses and withdraw upriver to Nanjing. Chen ruled this out immediately. We stay and fight, he ordered.(2)

The morning of the following day, September 23, passed in almost unbearable tension as the sailors scouted the horizon for any traces of Japanese planes. At 10:30 am two aircraft appeared in the distance. They seemed to be on a reconnaissance mission and soon vanished again. The actual attack didn’t happen until shortly after 2 pm. The first thing the Chinese sailors noticed was a group of about a dozen planes appearing over the southern horizon, heading north. They passed over the warships at a considerable height, without dropping any bombs. It was all a diversionary maneuver. Seconds afterwards, a larger force of low-flying planes appeared to the east over the Yangtze, swooped down over the First Fleet, and released their bombs.(3)

This time, the Ninghai was the focus of the Japanese attention. It suffered considerable damage and started to take in water. Teams of sailors worked frantically to repair the damage even as Japanese planes continued their attacks. After about 30 minutes, Chen Jiliang reversed his command from the night before and ordered the Pinghai to weigh anchor. The Ninghai was immobile, as an explosion had damaged it windlass, but eventually the cruiser’s captain ordered the anchor chain cut, and the ship started steaming upriver.(4)

For both cruisers it was too late to escape. The Japanese planes continued their merciless attacks on the slow-moving vessels, causing horrific damage. An officer on the Ninghai was standing at his post on the navigation bridge when a piece of shrapnel tore his head open, spraying the room with his brains. Pinghai was sunk by Japanese bombs late on September 23, and Ninghai the day after. Both met their end in shallow water, their hulls sticking out of the Yangtze for months afterwards as testimony to the Chinese defeat. (5)

It was the brief, violent, sad end of the First Fleet. For some Chinese naval officers it was too much to bear. When Hairong, an ageing German-built cruiser, was ordered scuttled near Jiangyin at the end of September, its captain Ouyang Jingxiu decided enough was enough. “Watching a large part of our ships go to the bottom of the river, taking all their weaponry with them, caused bigger pain for me than I could have possibly imagined,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I was already well advanced in my career, and I decided it was time to retire. That was the end of my decades spent in the service of our Navy.”(6)

Notes:

(1) Ma Junjie. Zhongguo Haijun Changjiang kangzhan shiji [A Record of the Chinese Navy’s Anti-Japanese Battles on the Yangtze]. Jinan: Shandong Huabao chubanshe, 2013, pp. 183, 185.

(2) Ma Junjie, pp. 186-187.

(3) Ma Junjie, pp. 188-189.

(4) Ma Junjie, p. 189.

(5) Chen Hui. “Jiangyin fengxiaoxianshang de zhandou” [“The Struggle on the Jiangyin Barrier Line”], in Nanjing baoweizhan: Yuan Guomindang jiangling Kangri Zhanzheng qinliji [The Defensive Battle for Nanjing: Personal Recollections from the War of Resistance against Japan by Former Nationalist Commanders]. Beijing: Zhongguo wenshi chubanshe, 1987, p. 59. Both vessels were raised by the Japanese and refurbished for use in the Imperial Navy. They were sunk again, this time for good, by US forces within months of each other in the fall of 1944.

(6) Ouyang Jingxiu. “Jiangyin fengjiang zhanyi jishi” [“A Record of the Battle of the Jiangyin River Barrier”], in Nanjing baoweizhan: Yuan Guomindang jiangling Kangri Zhanzheng qinliji, p. 56.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply