Jiangyin 1937: Battle for the Yangtze, Part 1

- By Peter Harmsen

- 22 December, 2015

- No Comments

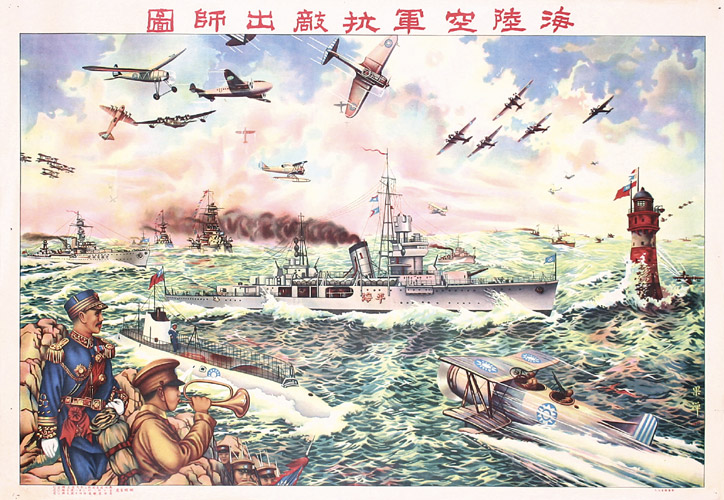

The first months of war between China and Japan in the fall of 1937 took place mostly on land and in the air. But the two nations’ navies also clashed in a fierce battle over the strategic city of Jiangyin on the Yangtze River. This is the first in a two-part series about this crucial, but forgotten episode in the history of the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The city of Jiangyin, roughly midway along the Yangtze between Shanghai and the capital Nanjing, was still far behind the front line in the fall of 1937, but it was of primary strategic importance. This was all due to geography. It was located at a point in the Yangtze where the river narrowed dramatically from up to three miles across to just about one mile. It had been known for centuries as the “true mouth of the Yangtze,” and it was a vital chokepoint for traffic further upriver. It marked Nanjing’s first line of defense.(1)

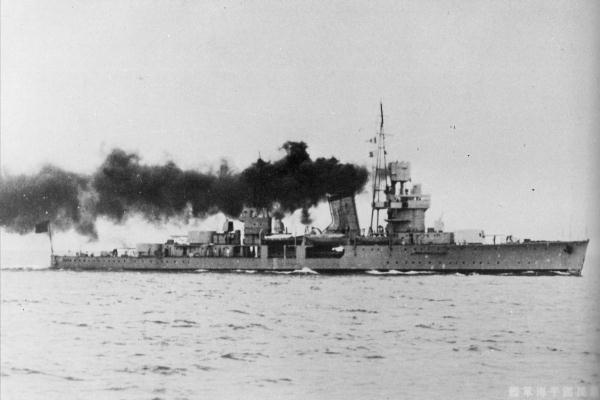

Accordingly, when the battle of Shanghai was about to break out in August 1937, the Chinese Navy went ahead with contingency plans to improve the natural barrier by sinking a number of mostly outdated vessels at a large island in the Yangtze near Jiangyin. (2) Admiral Chen Jiliang, commander of the Chinese Navy’s First Fleet, was given the task of overseeing the establishment of the barrier. In the evening of August 12, just hours before operations began in Shanghai, he boarded his flagship, the light cruiser Pinghai, anchored off Nanjing. Minutes afterwards, the signal flags went up: “All ships, anchors aweigh!”(3)

Within the hour six vessels of the First Fleet, including Pinghai and its sister ship Ninghai, were on their way through the gathering darkness towards Jiangyin. They arrived in the middle of the night. There was a reason for the haste. A number of Japanese warships had been sighted upriver. If the planned barrier could be put in place fast, they would be trapped, and they could be taken out one after the other.(4)

As dawn rose over Jiangyin, the sailors of the First Fleet caught sight of a group of ships moving downriver towards them. They quickly realized they were looking at the very Japanese ships they had been hoping to trap. In the lead of the small flotilla was the 280-foot hull of minelayer Yaeyama. Someone, possibly a spy in the Chinese command, had alerted the Japanese to the impending Yangtze barrier, and they were rushing to get out before it was too late.

This was a surprise, and the Chinese had no plan for what to do next. There was a need to improvise, but the unknowns piled up. Had war already started in Shanghai? Should the Chinese fire? Instead of firm action, paralysis set in. An almost surreal situation followed as the Japanese ships sailed past the line of Chinese vessels. The crews on both sides stared at each other across a few hundred yards of water, expressionless and without a sound. No shot was released, and the Japanese escaped to the ocean.(5)

After this anticlimax, the Chinese Navy set about the work of erecting the barrier. Seven old warships were scuttled to form the main obstacle. It was a rush job, and it involved some vessels that Chinese commanders later acknowledged shouldn’t have been included. Two of them, Desheng and Weisheng, were approaching obsolescence, but they could still have packed a punch against the Japanese Navy, and moreover, had a shallow draft that could have allowed them to operate on the Yangtze all the way up to the city of Chongqing. When learning that these two valuable ships had been sent to the bottom of the Yangtze, Chiang Kai-shek expressed deep regret.(6)

In the months that followed, the Japanese Navy showed up repeatedly near Jiangyin. In an ominous incident in late September, an enemy ship was sighted sounding the depth of the Yangtze, possibly in preparation of a landing.(7) Nevertheless, as far as the First Fleet was concerned, the main threat throughout the fall months came from the air, as Japanese planes occasionally launched small raids on the vessels anchored in the river.

The First Fleet had the ability to fire back, and it did so not just when it was attacked, but also when Japanese bombers passed overhead on their way to Nanjing. The naval gunners scored several hits. On one occasion, a Japanese pilot managed to eject after he was shot out of the sky. The sailors watched his parachute land safely on the bank of the Yangtze, and they speedily sent off a landing party. He was an intelligence asset and was needed alive. They found him before the local peasants could get to him, in which case he would have been killed immediately. Instead he was dispatched to Nanjing.(8)

Notes:

(1) Kessler, Lawrence D. The Jiangyin Mission Station: An American Missionary Community in China 1895-1951. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996, pp. 6-7, 116-117.

(2) Kessler, pp. 6-7, 116-117.

(3) Ouyang Jingxiu. “Jiangyin fengjiang zhanyi jishi” [“A Record of the Battle of the Jiangyin River Barrier”], in Nanjing baoweizhan: Yuan Guomindang jiangling Kangri Zhanzheng qinliji [The Defensive Battle for Nanjing: Personal Recollections from the War of Resistance against Japan by Former Nationalist Commanders]. Beijing: Zhongguo wenshi chubanshe, 1987, p. 53. Hereafter cited as NBZ.

(4) Ouyang, p. 53.

(5) Chen Hui. “Jiangyin fengxiaoxianshang de zhandou” [“The Struggle on the Jiangyin Barrier Line”], in NBZ, pp. 57, 59.

(6) Ouyang, p. 54.

(7) Zhang Yiyan. “Jiangyin kangzhan de houyuan huodong” [“Reinforcement Activities during the Defensive Battle for Jiangyin”], in NBZ, p. 102.

(8) Ouyang, p. 54.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Leave a Reply