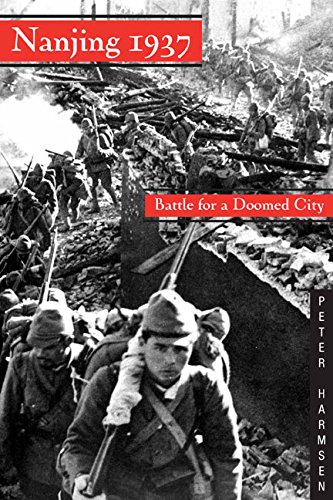

Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City

- By Peter Harmsen

- 13 November, 2015

- 4 Comments

‘Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City’ by Peter Harmsen is now on sale. The sequel of his best-selling ‘Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze’, it tells the epic story of China’s desperate defense of its capital Nanjing against a highly mechanized and determined Japanese foe in the fall of 1937. It is the first time that the campaign is the subject of an entire book in any western language, giving the pre-history of the infamous Rape of Nanjing. Below please find an excerpt from Chapter 1. You can order the book here.

‘Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City’ by Peter Harmsen is now on sale. The sequel of his best-selling ‘Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze’, it tells the epic story of China’s desperate defense of its capital Nanjing against a highly mechanized and determined Japanese foe in the fall of 1937. It is the first time that the campaign is the subject of an entire book in any western language, giving the pre-history of the infamous Rape of Nanjing. Below please find an excerpt from Chapter 1. You can order the book here.

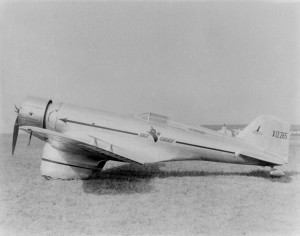

The three Chinese attack bombers rolled down the runway as night was reluctantly releasing its chilly grip over the airfield. Each of the American-built Northrop Gamma 2E monoplanes carried a pilot and a rear gunner and was armed with a 1,600-pound bomb. The angry, wasp-like hum of the Cyclone 9 engines filled the air as they took off. Soaring rapidly into the starless sky, the aviators could make out the familiar contour of the capital Nanjing, dark and brooding in the wartime blackout. A little beyond was the metallic gray of the Yangtze, moving relentlessly east towards the ocean. The planes were also heading east. Their objective that autumn morning: to search for Japanese vessels in the East China Sea and attack them.

At the controls of Northrop Gamma No. 1402 was Second Lieutenant Peng Deming of the 2nd Bomber Group’s 14th Squadron. Aged 24, he was already a veteran of the air battles that had raged over east China since full-scale hostilities with Japan had broken out that summer. Sitting behind him was his rear gunner, Li Hengjie, who was of the same rank but one year older. Both men knew the war wasn’t going well for China. After three months of intense fighting in and around the nation’s largest city, Shanghai, it was now only a question of time before the Japanese Army would break out and swarm across the nation’s prosperous and densely populated heartland.

They also knew what was at stake. It was right there below them. As the planes steered towards the thin sliver of dawn forming over the horizon, the faint light unveiled a never-ending patchwork of small, well-kept rice paddies, watered by intricate networks of irrigation channels. Villages formed tiny dots, spaced out at a distance of no more than a mile from each other. There were also larger commercial towns, many of them ringed by ancient city walls. It was a part of China that had been inhabited for centuries, and this early morning it looked as tranquil as ever. However, the peace would soon be shattered and serenity replaced by the turmoil of the battlefield.

It wasn’t long before the aviators saw the first signs of war. As they got closer to the front line near Shanghai, the country roads started filling with soldiers. They were dressed in the gray, khaki and blue uniforms of the loosely coordinated divisions and brigades that made up the Chinese Army. There were tens of thousands of them, and they were in full retreat. While they were withdrawing from Shanghai, a small number of their comrades-in-arms manned a thin defensive line to keep the Japanese at bay. It was the end of a battle that had consumed tens of thousands of lives over the past three months, and even as the Chinese tried to disentangle themselves, the killing continued. Columns of black smoke lined the roads where Japanese airplanes had swept down and dropped their deadly loads.

For Second Lieutenant Peng, the war was a very personal thing. All through his childhood, China’s escalating rivalry with Japan had rumbled in the background. In his late teens, while he had attended vocational high school in Shanghai, he had seen with his own eyes how frictions had intensified as Japan had tried to impose its economic and military might on China with growing boldness. Five years earlier, the situation had spiraled out of control and triggered the first major armed clash between the two nations, laying waste to large parts of Shanghai. Peng had wept bitterly when the fighting had ended in a draw, and not, as many Chinese had hoped, with the ousting of the hated Japanese.

Now a new conflict had begun, and this time a far larger number of Chinese were prepared for a fight to the death. They included Peng and his rear gunner Li, who had both graduated with Class 6 from the Central Aviation School in the east Chinese city of Hangzhou in the summer of 1937, just in time to be sent into battle when the war began. Hostilities had begun in the north of China and then spread to Shanghai. Peng had been sent on sortie after sortie, mostly targeting Japanese vessels bringing troops and supplies to the Shanghai front.

Despite the daily horrors he had to endure, the young man had enjoyed himself during the first dramatic stages of the Sino-Japanese War. “It’s an amazing feeling when you have completed a mission to return to base and be greeted by a cheering crowd,” he wrote in a letter to his parents. However, those heady days were well in the past. By late fall, the Chinese Air Force, which had only been set up a few years earlier and had suffered from having a succession of foreign advisors of inconsistent capability and commitment, had been wiped almost clean out of the sky. The 2nd Bomber Group consisted of a mere five planes and Peng and Li had lost many friends.

These losses were a source of great sadness, but they couldn’t allow emotions to compromise their ability to carry out their duty. That November morning they were focused on their mission. It had been raining for a week, but the forecasters had promised fine flying weather. For the first part of the mission, overland, they had been proven right, but when the formation approached the East China Sea, the sky became overcast. That was both good and bad. It greatly diminished the risk that Peng, Li and the two other crews would be discovered and hunted down by faster and nimbler Japanese planes. On the other hand, their own hunt for targets would also be more complicated.

Putting the coastline behind them, they steered their light bombers towards the Zhoushan islands, a small archipelago about ten miles from the mainland. Flying in a loose formation, the aviators constantly scoured the almost uninterrupted cloud carpet below, looking for holes where the dark blue ocean showed and where a trained eye might spot a potential target. By mid-morning, they were in luck. Three and a half hours after take-off they eyed a narrow opening in the clouds, and in the middle of it, an enemy aircraft carrier. There was no doubt that this was the opportunity they had been hoping for.

Peng positioned his airplane for a dive attack against the vessel. Coming in at an angle of slightly more than 30 degrees, the Gamma accelerated to close to 250 miles an hour. Tracer bullets sailed through the air towards it, as Japanese sailors opened fire in a desperate attempt to take him out before he could do any harm. It didn’t affect Peng, and he stayed on course. With the rapidly increasing outline of the ship in his bomb targeting sight, he was waiting for the exact right moment to let go of the bomb. It was an immensely difficult task, requiring him to allow for not just the course and speed of the ship, but also for his own speed and approach angle and the direction and strength of the wind. Praying for the gods of fortune to be on his side, he released the bomb, feeling the airplane lift abruptly as it was relieved of the heavy load it had been carrying since the start of the mission. He pulled away fast to escape the dense small-arms fire from the ship. The two other Gamma 2Es performed the same maneuver.

At a safe distance, the crews of the three aircraft tried to get an idea of the effect of their attack. With only three bombs among them, they would consider the attack a success if only one had struck the target. It had. Flames licked the stern of the ship, and a cloud of smoke was rising from the aft deck, as small figures in white sailors’ uniforms darted around in apparent confusion like ants from a suddenly exposed anthill. The sight set off triumphant cheers in the cockpits. Satisfied that they had been able to inflict a serious blow to the enemy, they soared above the clouds and set course for the Nanjing base.

The three bombers were making their way back at a cruise speed of slightly above 200 miles an hour when the airmen’s greatest fear materialized in the shape of two Japanese A5M monoplanes, which suddenly appeared out of the clouds. The Northrop Gamma had shown time and again in recent months that it was no match for the new generation of faster, more maneuverable Japanese fighters. The three Chinese aircraft had no hope of winning in a dogfight, and they could also not outfly their adversaries.

What happened next took only seconds. Peng noticed from the corner of his eye that one fellow Northrop Gamma pilot performed the only maneuver feasible at that point, carrying out a steep dive into the clouds before disappearing. The other Northrop Gamma was hit by Japanese bullets and plunged towards the ocean, wrapped in a coat of brightly colored flame. Neither of the two Chinese on board managed to bail out before the aircraft collided against the surface of the sea.

Then the Japanese pilots turned on Peng’s plane. Their bullets tore into the fuselage, causing dense, thick smoke to come pouring out. The burning aircraft rapidly lost height, and struggling to escape, Peng and his rear gunner managed to push back the canopy. They jumped out, releasing their parachutes. Floating slowly down towards the blue expanse below them, they watched their plane crash into the ocean. The only thing that could have saved them would have been a fast and efficient search-and-rescue operation. China didn’t have those capabilities in late 1937. The two were never seen again.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Thank you for your impressive book, I just finished in it 2 days (also loved your book on the Shanghai battle). For the sensitive and tragic subject of Nanjing, the existing literature usually centered on the horrible atrocities and the massacre itself. The military aspect usually being a afterthought. I’m glad there’s finally a book that focuses on the military situation of both sides.

My question is what is the estimated combat casualties for the Japanese army throughout the campaign?

And where there any recorded pockets of resistance either by individual units or stragglers after the city fell?

Thanks again.

Good questions – I’ll address them in separate posts on this website in the near future.

My compliments for Your writing style! I strongly hope Your books will be traduced in italian, because english, unfortunately, is not my language and i’m afraid to miss feeling.

I would like to read more about events as dramatic as unknown or forgotten (for western history) as 2nd sino-japanese war. I love both cultures, i just want to know more about those terrible years.

Thank You, best regards.

P.S. sorry for my broken english.

Just finished this book, great followup on the Battle of Shanghai. Good analysis and sourced from all sides of the conflict, Chinese, Japanese, and Western. As with the previous books, a good balance of the geopolitical situation, the war from the general’s perspective, the everyday man, and the individuals caught up in the day to day struggles. Of course, I’m now expecting you to write one on the battle of Wuhan!