What Shall We Call Chiang Kai-Shek?

- By Guest blogger

- 13 March, 2015

- 2 Comments

This article by historian Robert Bickers on Chiang Kai-shek’s relationship with the British at the start of his career was first published on his blog. It is reproduced here with his kind permission.

This article by historian Robert Bickers on Chiang Kai-shek’s relationship with the British at the start of his career was first published on his blog. It is reproduced here with his kind permission.

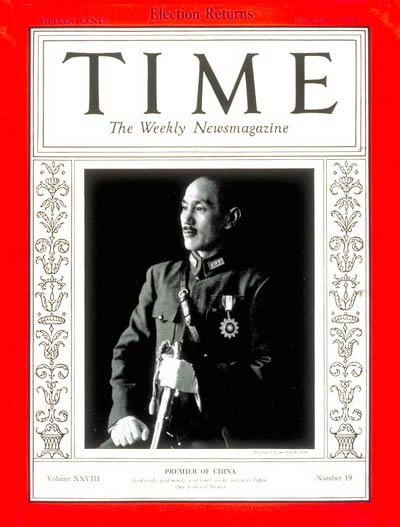

Tortoise? Leech? Snake? In the later 1930s, and especially during the 1941-45 Pacific War, Chiang Kai-shek was ‘the Generalissimo’, and was routinely and even fulsomely praised by British and US commentators. He and his wife, Song Meiling, graced the cover of Time magazine at least a dozen times. This positive view somewhat declined towards the end of the war — though not in Time — , and then dramatically so thereafter, as perceptions of incompetence and corruption amongst the Nationalist elite started to take root. Back in 1926-27, however, there was no love lost between British observers and Chiang. His diaries show his own hatred in this period for the British, who had intervened militarily at Canton, where Chiang and the Nationalist Party were building up the revolutionary base from which they would set out on the ‘Northern Expedition’ to unite China. British, as well as French, marines and armed volunteers, had killed over 70 National Revolutionary Army cadets and Nationalist supporters during the 23 June 1925 ‘Shakee massacre’ . Chiang was the ‘Red General’, the British felt, and a Russian stooge to boot, subject in their eyes to the authority of the leading Comintern operative in Canton, Mikhail Borodin.

In late January 1927, the issue of how to portray Chiang became urgent for staff in the Intelligence Office (later Special Branch), of the Shanghai Municipal Police. They were working loosely in alliance with the anti-Nationalist forces who controlled the city, who Chiang’s army was moving on to confront. Chief Detective Inspector Pat Givens, a Tipperary man, had a chat with his Chinese staff, and filed a report to Scotsman William Armstrong, Director of Criminal Intelligence.

The Chinese attached to the Intelligence Office … believe that the wickedness of General Chiang Kia [sic] Shek can only be brought home to the lower, uneducated classes by representing him as an unscrupulous, avaricious and blood thirsty traitor.

To really hammer home the message they felt it was

essential to disseminate cartoons representing him alternately as a tortoise, a leech, a cobra, a wolf and a “running dog”.

Armstrong forwarded the note to the Commissioner of Police, E.I.M. Barrett, remarking that ‘This form of propaganda is that employed by the Nationalists themselves’, and that it was ‘very effective and is easily understood by those whom it is intended to reach’. The report was written in response to a newspaper article describing posters with caricatures like this being pasted up all over the city, and which argued that they were too crude and merely amusing people.

It is not explicitly clear from the file containing this note that the police force itself was behind the campaign, but it is quite strongly implied, and it was all in a day’s work for a Shanghai policeman during a revolution that they opposed. However, attitudes amongst the British changed rapidly once Chiang purged communists and leftists from the party in a series of bloody manoeuvres later that Spring, after his forces had taken the Chinese-governed parts of the city. Givens, a later account noted, was ‘the first official of the Settlement to welcome General Chiang Kai-shek’ (North China Herald, 25/03/1936). The Shanghai Municipal Police would work very closely in the 1930s with the Nationalist policing authorities, as they waged a quite successful campaign against the Chinese Communist Party and Soviet and Comintern agents. T. P. Givens rose steadily within the force. William Armstrong perhaps felt too compromised by his close collaboration with the anti-Nationalist forces, and quickly left Shanghai, retiring in June 1927. And so it went on: enemies had turned allies, and allies turned enemies as Chiang’s forces crushed the Communist Party and the Comintern teams fled. And so the Chinese wolf lay down with the British lion.

Source: SMP Special Branch files, US National Archives and Records Administration, NARA RG263, file IO7563, 27 January 1927.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

Are we just ignoring the fact that CSK was, in 1927, indeed a Russian stooge? He wasn’t a generalissimo and he wasn’t in charge, that came much later.

British intelligence agents had no respect for Chiang Kaishek, operating in China without checking in with the Chinese government first, so of course CKS never cooperated with British intelligence. The British secret dealings with the Tibetans, too, raised eyebrows. The Brits gave CKS enough reasons to be suspicious.

CIA, too, had no respect for the Chinese, and CKS nearly kicked all CIA agents out of China during war time.

But to say Chiang is uncooperative with all western intelligence agencies is unfair. Take a look at Dai Li’s close working relationship with US Navy intelligence and you will see that it isn’t hard to work with CKS’s government. One only needs to view the Chinese shoulder-to-shoulder. Too many westerners during that time period view the Chinese as an inferior race, and they couldn’t figure out why the Chinese wouldn’t work with them!