Radio Free China

- By Bill Lascher

- 27 March, 2014

- 1 Comment

This article on how a sleepy California beach town was at the center of a war across the Pacific is excerpted from Boom, a Journal of California. For the full story, click here

This article on how a sleepy California beach town was at the center of a war across the Pacific is excerpted from Boom, a Journal of California. For the full story, click here

The newsmen ignored the Japanese bombs shaking seventy-five feet of rock above their heads. It was June 1940, and a team of Chinese and Western broadcasters continued their reports from a tunnel beneath Chongqing, China’s wartime capital, the “world’s most bombed city.”

Seven thousand miles away, in Ventura, a dentist woke early to listen to their broadcast. As he did every morning, beginning precisely at 5:53 a.m., Dr. Charles Stuart spent two hours carefully monitoring recording levels as acetate discs recorded the broadcast from XGOY, the Chinese government’s radio station. Next to him, wearing dental assistant whites and huge headphones pressed to her ears, Stuart’s secretary—and wife—Alacia Held, transcribed every word. Finally, a familiar farewell closed another day’s broadcasts.

“XGOY is signing off now,” declared Melville Jacoby, a twenty-three-year-old freelance journalist hired to compile and read the station’s broadcasts. “This is the Voice of China, the Chinese international broadcasting station, Szechuan, China. Good morning America and goodnight China.”

…

Without Doc Stuart’s radio towers on the California coast, his dedication and technical mastery, China may have been completely isolated from the outside world. So crucial was his work to the Republic of China’s war effort that it awarded him its highest civilian honor, the “Special Collar of the order of the Brilliant Star.” At the time, he was the only foreigner to receive the award.

…

The major networks, with their expensive equipment and technicians, had struggled for years to bring in XGOY. But finally, as Harrison Forman wrote for Collier’s in 1944, major US networks “admitted they’d never met a better man and ran their lines into Doctor Stuart’s little attic. Now every word and note that America hears from Chungking is funneled through that attic.”

Newspapers across the country covered Stuart’s efforts throughout the war. NBC itself lauded him in a 1945 broadcast. When General Douglas MacArthur radioed Japan’s emperor for surrender terms, he sent a copy of the message through Stuart to make sure it reached appropriate parties. Stuart even received Chinese honors reserved for dignitaries.

Chongqing, China’s wartime capital, was devastated by sustained Japanese bombing. Photograph courtesy of the estate of Melville J. Jacoby.

“He proved to be both technically well-equipped to handle the job and faithful in the performance of a function which he voluntarily took upon himself,” Chinese information minister Hollington Tong later wrote, also noting Alacia’s role in the news operation. “The Stuarts performed a basic and essential service for us throughout six years of war.”

…

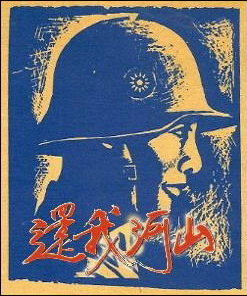

During the war, Chiang Kai Shek’s Kuomintang government operated a complex propaganda and public relations effort aiming for sympathy—not to mention funding and favorable policy—from allies in the United States. The strategy depended on XGOY and its signal reaching the West, but the station had to transmit through Japanese bombs and interference to disseminate official messages to sympathetic editors, philanthropists, and foreign officials.

…

Aside from its political importance, XGOY became one of the only ways a tight cadre of foreign journalists could reach newspapers, magazines, and radio networks back home. The station transmitted a weekly “mailbag” of messages from Americans in Chongqing that Stuart relayed to their American family members. At one point, XGOY even broadcast the text, punctuation and all, of an entire book—China After Five Years of War—so it could be sent to New York in the middle of the conflict.

But for any of these messages to reach the United States, XGOY needed more than skilled broadcasters in China; it needed a radio expert—preferably one in California—who could locate their faint signal while advising them on how to improve their transmissions.

They needed Doc Stuart.

….

Stuart’s work for the Chinese began in 1940, when the Chinese News Association, a Kuomintang-run press syndicate based in New York, dispatched Earl Leaf to find someone to receive broadcasts from XGOY. At the time, Leaf was “an ex-logger, miner, cowboy, sailor and accountant” who had worked for the United Press and was one of the first Western journalists to meet and interview Mao Zedong. He worked his contacts in California and soon learned that if anyone could help the Chinese, it was Doc Stuart.

It was only through Stuart’s guidance that the Chinese information ministry was able to prevent heavy Japanese interference and the 7,000 mile distance across the Pacific from garbling news broadcasts meant for American audiences.

…

Working for XGOY, Stuart became an ardent partisan in China’s resistance to Japanese invasion. Stuart didn’t hide his support for the Kuomintang. He was the local chair of United China Relief, an organization set up by Luce and Selznick. When President Roosevelt omitted China from a list of major battlefronts during a speech in 1942, Stuart wrote a pointed letter of complaint to the president.

“Do you realize how great a boon this failure to recognize China’s effort is to our Japanese antagonist,” Stuart wrote, warning that Free China was the lone force preventing what he described as an all-out “racial war” with the United States from erupting in Asia.

“China’s has been a thankless struggle; a struggle which is without parallel in history; a struggle alone; a struggle against unprecedented odds with self-professed friends, true, who through four and a half years supplied her enemy, Japan, with the major portion of the sinews of war,” Stuart continued. “We then found it easy and convenient, and I may add profitable, to supply our enemy. We now find it difficult to supply our friend.”

Bill Lascher is a writer and multimedia storyteller currently working on a book about World War II-era journalist Melville Jacoby. Read more here.

Copyright © 2025

Copyright © 2025

So interesting to read the article about my Godparents, Charles and Alacia Stuart. Nice to see their story continues. My mother ‘babysat’ the two sons while they were in China. They had quite a time while they were gone too.